Having discussed few related ‘good examples’ from the past, now let’s have a look at what’s around in terms of aerial warfare in Ukraine. This is something like ‘easiest’ part of this story, then most of the equipment is well-known, and many like to have some sort of ‘metrics’ involved – and think there’s no better metrics than equipment and its numbers.

At the ‘top’ – at the command and control level – the ‘team Russia’ is operating:

- Over-the-horizon radars (like 29B6 Kontayner, or Podsolnukh-E and Laguna-I);

- 7-8 Beriev A-50 (ASCC/NATO reporting name ‘Mainstay’) airborne early warning aircraft (AEW; abbreviated with SRDLO in Russian);

- about a dozen of signals intelligence- (SIGINT) and electronic intelligence- (ELINT) -gathering aircraft, like Tupolev Tu-214/214R and Ilyushin Il-20;

- foremost, the Russians have a broad array of ground-based communications intelligence-(COMINT) -gathering systems, and a large number of electronic warfare systems, which they are also using for ELINT and SIGINT, and

- the Russians have something like full air defence army deployed in and around Ukraine, including few dozens of SAM-brigades equipped with S-400 (SA-21), S-350 (SA-28), S-300 (SA-20/23), Buk (SA-17/27), Tor (SA-15), Pantsyr (SA-22), even few Osa-AKM (SA-8) and Strela-10 (SA-13) systems, all of which are operating their own surveillance radars and fire-control radars…

The ‘team Ukraine’ is actually including two-, or even three ‘teams’:

1.) Ukrainian Air Force (PSU, which is including Ukrainian ground-based air defences) is operating its own long-range surveillance- (also ‘early warning-’) radars, plus surveillance- and fire-control radars of its MIM-104F Patriot (PAC-3CRI, with few PAC-2s), S-300PS and S-300PMU (SA-10/20), NASAMS, IRIS-T SLM, 2K12 Kub (SA-6), Buk (SA-11), Tor (SA-15), Crotale NG, MIM-23 HAWK, Osa-AKM (SA-8), Aspide/Sky Guard/Spada, S-125 Neva (SA-3), RBS-70 CIWS (with Giraffe 40 radars) etc., etc., etc.

2.) Ukrainian intelligence services are operating a number of COMINT/ELINT/SIGINT-gathering systems and a number of electronic warfare systems (which they’re also using for COMINT/ELINT/SIGINT-gathering purposes).

3.) NATO, which is operating reconnaissance satellites (all subjected to the control of different national intelligence agencies);

- at least one over-the-horizon radar (the French NOSTRADAMUS, if operational),

- a total of 18 NATO-, 31 USAF-, and 4 French Boeing E-3 Sentry Airborne Early Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft, and

- a plethora of communications intelligence- (COMINT), ELINT, and SIGINT-gathering-systems (some of these on airborne platforms, like Boeing RC-135 or Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk UAV; others in form of a wide diversity of ground-based platforms).

At the first look it might appear this is resulting in a ‘chaos’: lots of command nodes, lots of detection- and reconnaissance platforms, lots of different SAM-systems…. Actually, regardless what service is operating what of listed systems, both sides are striving to integrate all the systems in question in order to get what is called the ‘big picture’ - like our brains are using eyes, ears, noses, and fingers to find, track….and do whatever we find necessary doing with things of our interest.

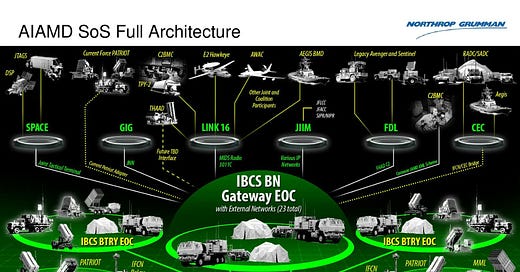

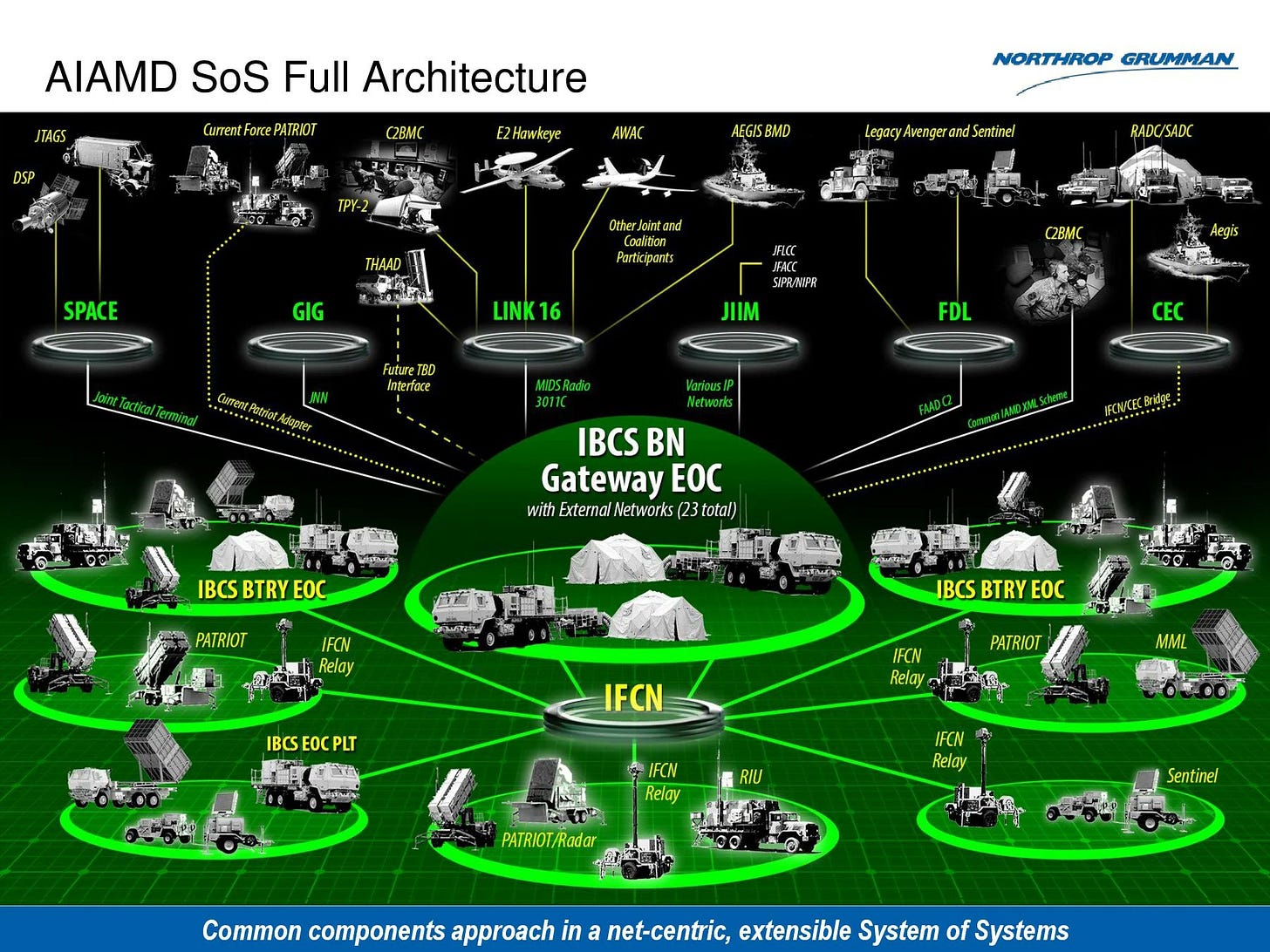

Nowadays, that’s called ‘network centric warfare’ and is supposed to provide commanders with superior situational awareness: to enable them to coordinate operations of all available units and weapons systems. Correspondingly, all the platforms in question are integrated with help of data-links into networks (the power of which is putting any of civilian-operated internet connections into a deep shade). The resulting information is fused into integrated battle command systems (IBCS’).

For example: PSU used to operate its own, domestically developed integrated air defence system (IADS) already well before the all-out invasion of February 2022. Atop of this, word is that ever since the USA delivered its Nothrop Grumman AIAMD to Ukraine: this is an IBCS including powerful computers and communication systems that are fusing the work of all available sensors, reports by intelligence services, ground-based radar stations, AWACS aircraft, ground based air defences, ground troops, naval units… etc., etc., etc. – regardless if these were originally designed to work together or not. If so, the PSU is nowadays enjoying the services of a vastly superior IADS than all of Russia has, with plentiful of redundancy (something that’s always nice to have in combat, just like an extra bag of ammunition).

Some in the West think the Russians think slightly different about the affairs in question. Actually, they’re lagging – ever more – in the related disciplines already since the 1960s, they’re lacking necessary advanced technologies, and - because the Russians are people who like to plan, and discuss plans, but have a problem with actually realising these - are quarreling about how exactly to do that, all the time.

Sure, in the early 2000s, they initiated the work on what they call the ‘reconnaissance-strike complex’ (razvedyvatelno-udarnnyy kompleks, RUK) or the ‘reconnaissance-fire complex’ (razvedyvatelno-ognevoy complex, ROK). Multiple projects were launched, but it appears that only two were actually realised. At the strategic level, since around 2014-2015, there is the National Defence Management Centre (Natsionalnyy Tsenter upravleniya Oboronoy, NTUO) in Moscow. However, this battle command system is so far integrating only the work the Strategic Rocket Forces (RVSN) and commands of all the joint strategic commands of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (OSKs of the VSRF).

The planned integration of airborne (VDV), GRU Spetsnaz units, and ground forces (like the 6th and 20th Combined Arms Army and the 1st Tank Army) was to be completed by 2027. In regards of the Russian Aerospace Force….the Keystone Cops didn’t even think as far. Indeed, the integration of the NTUO with command nodes at operational and tactical level was never realised and – because of the lack of necessary technologies, production facilities, and know-how – that’s unlikely to change any time soon.

The second system they did manage to develop is the Automated Command and Control System (Avtomatizirovannyye Sistemy Upravleniya, ASU), which is in use in the headquarters of every of the joint strategic commands of the VSRF. Theoretically, the ASU is supposed to integrate the work of all air-, ground-, and naval units of the command node in question with help of the Unified System for Managing a Tactical Unit (Yedinaya Sistema Upravlieniya Taktichkogo Zvena, YeSU-TZ, which I’m simplifying with ‘ESU-TZ’).

Developed following the failure of the first Russian digital system of this kind (Metronome), the ESU-TZ was planned to become fully operational in all of the VSRF – and thus the VKS – by 2025. However, it suffered a series of delays: the Keystone Cops in Moscow, the GenStab, and the defence industry never worked together closely enough to coordinate all the related efforts. Actually, most of the time they were quarrelling over the design, parameters, and failures of the resulting software and equipment. Although undergoing testing at least since 2010, the ESU-TZ was de-facto abandoned by the GenStab around 2015, and then adapted for operations by artillery units equipped with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones), only.

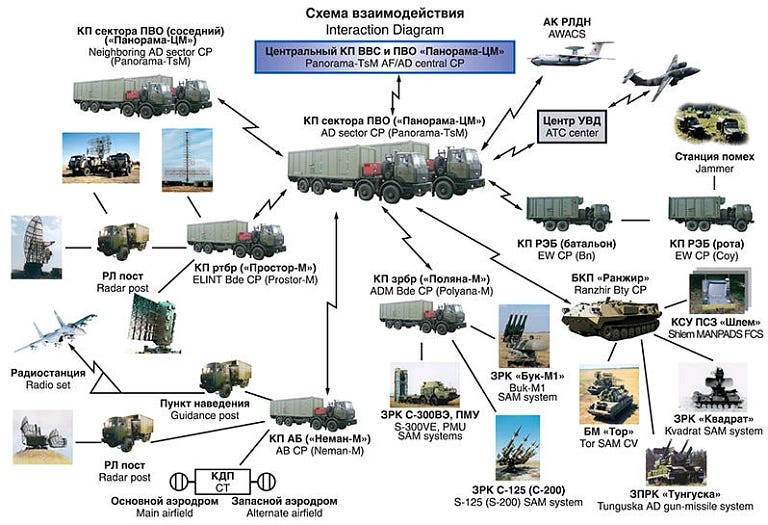

Result: the ESU-TZ is not communicating with the ASU of the OSKs, and even less so with the IADS of the VKS. Until today, I do not know about a single combat aircraft of the VKS having the ESU-TZ installed….which is ironic, because the VKS has a number of its own integrated air defence systems and automated tactical management systems in service already since the 1960s. Modern-day systems in question are such like UBKP Ranzhir (integrating the work of all elements of one SAM-site), Senezh (integrating the work of all units of a SAM-brigade), Polyana (integrating the work of multiple SAM-brigades), and Panorama (integrating the work of entire air defence armies)…

However, due to the obsolescence of their computers, systems in question are usually limited in terms of the number of own and enemy units they can simultaneously control and command - and: they are not integrated with the work of ground- or naval units.

…that much about equipment and theories….

Now, why is all of this important, how is it working, and what’s all of this looking like in practice? Indeed, what does this mean for air defence operations?

Considering all I’ve described above, it’s no surprise that to most of non-involved people modern air warfare appears a sort of ‘mystery’, including no little ‘wizardry’. Even more so considering that as humans, we grow up standing on the ground, moving forward, left or right, or back. Except for pilots, we’re not used to ‘moving up’: therefore, we think in three, not in four dimensions. Other widespread misconceptions about air warfare are that there is no cover up there in the sky, that radars are dominating everything, and that aircraft are still deployed, operated, and fighting, essentially, something like ‘Messerschmitts versus Spitfires’ during the Battle of Britain, back in 1940…

Don’t worry, it’s not too complex: essentially, air wars are fought in almost the same way like ground- and/or naval wars, on basis of exactly the same factors. See: geography, terrain, weather, manoeuvring, cover, availability of equipment and weapons, training, deployment of weapons etc.

Like in ground and naval warfare, fundamental issue in aerial warfare is that of ‘situational awareness’: of knowing and of being aware (or not), all the factors listed above, plus knowing (or not) where is the enemy, what are its capabilities and intentions. Situational awareness is decisive: if you know what, where, and how is your enemy doing, you can counter; if not, you’re in trouble. Indeed, one can say that the party with superior situational awareness is a near-certain winner, too.

This factor – the situational awareness – is the reason why I’ve started this part of my feature with description of command and control systems on both sides.

The question is: how to describe the situational awareness in air warfare ‘in a few words’?

Obviously, the principal issue of situational awareness it the issue of detection. Obviously, principal means of detection is visual. However, this is limited in range: this is why there is a widespread impression that for long-range detection (for detection outside the ‘visual range’), the air power (including ground-based air defences) is depending upon radars.

Moreover, people tend to think within realms of radars being something like ‘wonders’: if one powers up one, it is certain to ‘see’ – to detect – everything flying around it, all the way to its maximum range and elevation. That no aircraft nor other flying objects can hide… In reality (and oversimplified), it’s anything else than that.

It might appear as ‘going off topic’ at first, but: for me, the starting point of understanding modern aerial warfare was the statement by a gentleman who used to serve as – between others – a Combat Information Center Officer (CICO), or ‘Mission Commander’ on Grumman E-2C Hawkeye airborne early warning aircraft of the US Navy. Equipped with a powerful long-range radar, the E-2 is the equivalent to the ‘offensive/defensive coordinator’ in American football: the aircraft that serves as the ‘brain’ in the US Navy’s air warfare system. Its crew is tasked with having the big picture, the full situational awareness, knowing everything that’s necessary to know about both own and enemy forces, and thus expected to be in position to tell everybody else when, where, what, and how to do.

In turn, the officer in question described modern air warfare as a contest between two (or more) people, all equipped with hand-held lamps, on a darkened football stadium – by night.

What should that mean?

As said, people expect radars to detect everything. That no aircraft (or other flying objects) can hide. In reality, and oversimplified, it’s exactly the opposite. Due to physical laws and modern-day military equipment, powering up a radar is like if one of people on that football stadium by night has turned on his/her hand-held lamp: the owner of that ‘radar’ – i.e. the lamp – can only see what the light of the lamp enlightens. Depending on the power of that lamp, that might be 5-, 10-, 20-, or whatever metres far, and is usually limited in width. Nothing more.

However, everybody else on that stadium – even in its most distant corner, 50-, 100- or more metres away – can ‘see the light’; can see where is the owner of the lamp; even where is the owner of the lamp looking, heading, how fast is he or she moving – and what does the owner of the lamp see.

And that without turning their own lamp/s on, and thus remaining concealed.

This is so for reasons I’ve mentioned above: physical laws and modern-day equipment. One of the former is that radar signals can be detected from up to twice the radar’s maximum range. One of the latter is that all serious modern-day armed forces are striving to equip themselves with ELINT and SIGINT equipment: with tools enabling them to, between others, detect radar signals. Combined, oversimplified, and for example, this results in a situation where signals emitted by a radar advertised/expected to detect targets of certain radar cross section over a range of, say, 200km, are likely to be detectable from up to 400km away.

At the same time, radar is anything else than ‘certain’ to detect the enemy: performance of any radar remains influenced by the Earth curvature, climatic conditions and weather (especially clouds, rain, thunderstorms, sand storms…), terrain (mountains, sea state…), vegetation (trees…), man-made obstacles (tall buildings…), its power output, the size of its antenna, the function of the radar (for example: is antenna scanning 360 degrees, or less), and plenty of other factors.

With other words: a radar might detect an enemy aircraft (if there is one, and then if there is one within detection parameters), but it might detect nothing at all. The only thing certain is that any radar that powers up somewhere in Ukraine or western Russia of our days, is making itself detectable by the means of enemy’s ELINT and SIGINT. Worst of all: none of radars in question is ever going to be able to tell exactly who detected its emissions.

That is something like ‘Rule No. 1’, and this is why it can be said that modern-day air warfare is starting with an irony: billions are spent into development of ever more sophisticated radars, every year, and into development of aircraft and weaponry capable of evading radar detection – while, in combat, everybody is trying to reduce radar emissions and dependence on them to an absolute minimum.

….all of which shouldn’t mean that nobody is using radars at all. Quite on the contrary: that’s where things are getting ‘really funny’, definitely ‘interesting’…

(to be continued…)

Thank you very much! Extremely clear and understandable concerning complicated things. Looking forward to continuing.

It seems the Ukrainians should have the situational awareness advantage from NATO and USA assets but they lack the ability to act. Meanwhile the Russians have the means of action and sufficient situational awareness to carry out the actions in a limited capacity.

Would it be accurate to say that balance could easily shift if the Ukrainians were given the ability to disable Russian radar? Do they have sufficient airpower to achieve even local superiority?