Thanks a lot for bearing with me through the Part 1. I find so many positive reactions very encouraging – even more so because I feel that the Part 2 needs to follow in similar fashion.

For the start today, a ‘reminder’ on ‘vocabulary’:

- ARM = anti-radar missile

- CBU = cluster bomb unit

- ECM = electronic countermeasures

- ECCM = electronic counter-countermeasures

- GBAD = ground based air defences

- IADS = integrated air defence system

- IDF/AF = Israeli Defence Force/Air Force (official title, 1948-2004)

- SAM = surface-to-air missile

- SA-2 = Soviet-made S-75 (Dvina/Volga/Desna) SAM-system

- SA-3 = Soviet-made S-125 (Neva) SAM-system

- SA-6 = Soviet-made 2K12 (Kub/Kvadrat) SAM-system

- SEAD = Suppression of Enemy Air Defences

- SyAADF = Syrian Arab Air Defence Force (official title from 1973 until 2012)

- USAF = US Air Force

Yesterday, I’ve explained something about survivability of a single SA-2 SAM-site. Could go on with, probably, ‘dozens’ of similar examples – whether from the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War, or some other conflicts. I think, in this place it’s sufficient to mention just one more such example, though probably the best known one: the famous (and famed) Israeli Operation Mole Cricket 19, run on 9 June 1982, against the integrated air defence system (IADS) of the Syrian Arab Air Defence Force (SyAADF) deployed in central Lebanon. As is (more than) well known, the Israelis claimed ‘destruction’ of 19 Syrian SAM-sites within two hours of that afternoon. This is what you’re going to read in every single account of that action. What you aren’t going to read is that 14 of Syrian SAM-sites in question were fully operational on the next morning…

But, ‘repeating the exercise’ is not my favourite activity. Instead, today I would like to address something related to the title of this ‘mini-series’ of features: that with the ‘assault mode’. Don’t worry: that story is as under-published as the one of operational history of North Vietnamese, Egyptian, and Syrian SAM-operators (I’m, intentionally, avoiding the Soviets and the Chinese, because my colleague Krzysztof Dabrowski covered them so well in his excellent book ‘The Hunt for the U-2’).

***

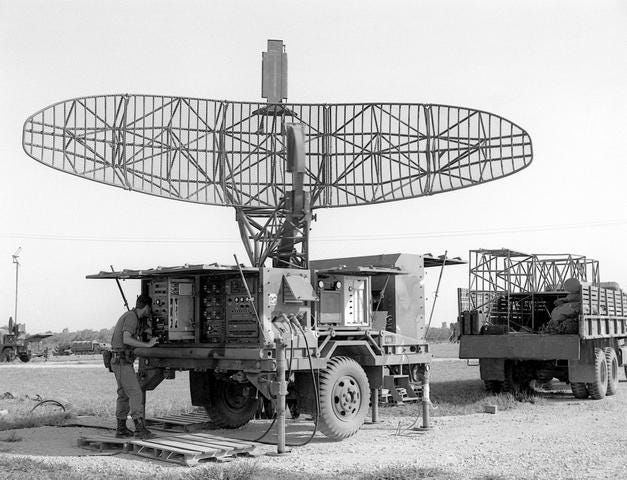

Around the same time the Soviets developed and launched production of their S-75 SAM-system (i.e. ‘SA-2 Guideline’), the USA developed a SAM system that eventually entered service under the designation MIM-23 Hawk. Like the SA-2, this included six towed launchers. However, every of six launchers had three launch rails. Means: a single MIM-23 SAM-site had a total of 18 ‘ready to fire’ missiles, instead of ‘just six’, like the Soviet SA-2. Foremost, except for a surveillance radar, the MIM-23 received two fire-control radars. Except for lots of command- and support equipment, trailers with re-loads, power generators etc., crucial elements of every MIM-23 ‘battalion’ or ‘site’ were something like this:

- 1x Pulse Acquisition Radar (PAR; later ‘Improved-PAR/IPAR’; surveillance radar)

- 2x High Power Illumination doppler Radar (HPIR; fire control radar)

- 6x M192 launchers with a total of 18 missiles.

- 6x power generators.

Means: right from the start, one Hawk SAM-site was capable of engaging two targets at the same time (compared to ‘one-target-per-SAM-site’-capability of the SA-2, SA-3, and SA-6). Moreover, instead of – essentially – ‘radio-command guidance with help of radar’, like in the case of the SA-2, the Hawk was utilising continuous wave (CW) guidance system. The same like ‘semi active radar homing’ in the case of air-to-air missiles. That means: its fire-control radars were tracking the target so that its missiles were (automatically) following target’s radar echo.

The MIM-23A was supplied to Israel in the mid-1960s: it came as a rude surprise for Egyptians, once they began facing it, after the June 1967 Arab-Israeli War (also ‘Six Days War’), and quickly earned itself fearful reputation within the Egyptian Air Force. By 1968, its effectiveness prompted the EAF into re-training much of its – meager – strike force of MiG-17F fighter-bombers into assets for so-called ‘Suppression of Enemy Air Defences’ (SEAD).

Arguably, the EAF had some 80-100 MiG-17Fs in service on average. This sounds as ‘much’. In terms of combat capability, it was very little. Sure, the small MiG was bellowed by its pilots and ground crews alike, for it was simple to maintain, highly reliable, and agile. However, originally it was designed as a high-altitude interceptor. At low altitude, it was very short ranged, and carried only a minimal warload. Maximum – for strikes out to a range of around 120-150km – included two bombs calibre 250kg and 8 unguided rockets. Foremost, MiG-17 stood no comparison to the primary Israeli ‘SEAD-weapon’: the F-4E Phantom II. It’s capability to carry external weapons was a far cry from Phatom’s capability to haul 3,000+ kilogram of bombs at a speed of 1,000(+) km/h over a range of 400+km… Indeed, a single F-4E Phantom could carry almost as much ammo and ordnance as an entire squadron of MiG-17Fs…

Their original task of Egyptian MiG-17s as of 1967-1968, was to strike ‘other’ Israeli ground forces: but, under the given circumstances, the entire ‘fleet’ had to be re-tasked into striking Israeli air defences instead.

One way or the other, already as of 1969, the situation in the War of Attrition along the Suez Canal was such that the Egyptians wouldn’t do anything at all, no matter where along the frontline or on the Sinai Peninsula – without first sending their MiG-17s to strike the nearest Israeli MIM-23 Hawk SAM-site. Their pilots excelled in flying at critically low altitudes (5-15m/15-90ft) and their strikes were quite effective: they, really, would hit every single time. Problem: the weaponry deployed by MiGs in their SEAD operations was too light. Their bombs calibre 250kg were ineffective (foremost because of the soft, sandy soil of the Sinai); causing next to no damage. Actually, pilots usually deployed them during their first attack run to scare the Israelis away: to force their MIM-23-crews into shelters. Most of damage was caused during their second attack run, when they would deploy unguided rockets and internal cannons calibre 23mm and 37mm to target HPIR fire-control radars of Israeli MIM-23s.

After about a year of such activity, the Egyptians concluded that their SEAD-strikes were shutting down the targeted MIM-23 SAM-sites for about 4 hours on average. That’s how long it usually took the Israelis to repair their HPIRs. In the few cases where the HPIR was completely destroyed, it would take the Israelis up to 12 hours to bring in a new one. In turn, dozens of MiGs were shot down and their pilots killed: few by Hawks, more by Israeli interceptors. Still, Egyptians had no options but to proceed that way: this went so far that when the War of Attrition heated on its ‘northern frontline’ (the one between Israel and Syria), in 1972, the EAF deployed its best SEAD-asset – No. 62 Squadron – to Syria, thus further depleting its meagre fleet of fighter-bombers. This unit remained there through the October 1973 War, and became the first to detect the presence of the Israeli MIM-23s on the Golan Heights, too…

Meanwhile, the reputation of the MIM-23 earned it an ‘upgrade’ of the nickname: from ‘Hawk’ to ‘Homing All-the-Way Killer’, HAWK. Moreover, sometimes between 1972 and early 1973, a new, much improved variant designated MIM-23B I-HAWK began reaching the Middle East. Never found the time to check whether the following became possible only through the appearance of that version, or not, but: the I-HAWK could be deployed in the so-called ‘Assault Mode’.

In such modus of operations, one SAM-site would be split into two elements: each of two HPIRs would then control three M192 launchers. Instead of one, the Israelis ‘suddenly’ had two SAM-sites. The total of 12 they’ve received by 1973 could be deployed as 24….

Moreover, based on Egyptian (and Soviet) SAM-operations from the War of Attrition, the Israelis learned to use their MIM-23s in ‘offensive’ fashion: they would quickly re-deploy one, two or elements of more of their SAM-sites very close to the frontline, activate it/them for a short period of time, and then quickly withdraw before the enemy could react with artillery or air strikes.

Ironically, the most successful Israeli ‘Assault Mode’ operation remains largely unknown: if at all, you might get to read about the flying supermen of the IDF/AF shooting down ‘lots of MiGs’, ‘on sight’, on that day. Actually… At the high point of the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War, during the night from 23 to 24 October 1973, the Israelis launched their attack into Suez City. This drive was supported by the deployment of at least ‘half’ of one of their MIM-23 SAM-sites in the Assault Mode, very close to their foremost troops. Thus, when the EAF scrambled no less than 32 MiG-21s to provide top cover for its fighter-bombers sent to attack enemy ground units, these found themselves facing an unexpected ‘missile wall’. No pilots could ignore SAMs flying in their direction. As their targeted jets began manoeuvring to avoid, Egyptian formations fell apart. Pilots lost ability to support each other. Were too busy even to search for enemy fighter jets. At that moment, they were hit by Israeli Mirages and F-4Es: the pilots of these claimed some 15 kills, of which 14 are considered as ‘confirmed’, at no loss for themselves. The Egyptians confirmed the loss of two MiGs to HAWKs and six to enemy interceptors…

Quite similar scenes occurred during the Second Iraqi-Kurdish War of 1974-1975. In that case, two units of the Imperial Iranian Air Force equipped with MIM-23B I-HAWKs and disguised as ‘Kurdish insurgents’ (even wearing their traditional robes) were deployed into northern Iraq. The Iraqi Air Force (IrAF) of the time was well-trained, combat experienced, and had a well-developed doctrine In ‘counterinsurgency’ (COIN) operations. Indeed, this was closely reminiscent of the US Air Force’s operations over South Vietnam (including forward air controllers flying Cessna O-1As acquired from the USA in the late 1950s). But, it had no clue about the presence of Iranian MIM-23s, and no means to counter them. Moreover, early on, none of its targeted crews survived to tell what has hit them. In a matter of weeks, the Iranians claimed 14-15 kills, including one against a high-flying Tupolev Tu-16 bomber. It was only at that point in time the Iraqis realised what are they facing. From that time onwards, the MIM-23B I-HAWK became known as the ‘Death Valley’ between pilots of the Iraqi Air Force…

A decade later, the Iraqis faced the ‘Death Valley’ again – during the war with Iran (fought 1980-1988). Initially: with almost the same results. The Iranians were all the time moving their ‘half SAM-sites’ around the battlefield, taking the enemy by surprise, and causing them losses. The situation reached such proportions, that Baghdad demanded urgent deliveries of Caiman and Remora ECM-pods, and Baz-AR anti-radar missiles from France: these were all ordered already before the war (indeed, in reaction to experiences from the Second Iraqi-Kurdish War). However, like all of Western powers, the French were preparing to counter the Soviet Union-led Warsaw Pact forces. Thus, they didn’t care to develop weapons that could counter US-made weapons. And, their technology was lagging behind that of the USA, which had plentiful of recent combat experiences from the Vietnam War. Thus, the French first had to develop all the high-technology necessary to make electronic warfare systems and anti-radar missiles ordered by the Iraqis, and then manufacture them…

First Baz-ARs have reached Iraq in 1981, but it took months for the French and the Iraqi Air Force to make them operational. Moreover, they were much more expensive than the Soviet-made Kh-28 anti radar missile (ASCC/NATO-reporting name ‘AS-9 Kyle’) meanwhile rushed by Moscow to Baghdad (the resulting ‘AS-9 vs MIM-23B I-HAWK Battles’ are a longer story, told here). The development of Caimans and Remoras took until 1984. By then, dozens of IrAF aircraft were shot down by Iranian HAWKs, or combinations of HAWKs and F-4 and F-14 interceptors of the Iranian Air Force. Once Caimans and Remoras were in service, though, they became the ‘go’ or ‘no go’ issue: essentially, for the rest of that war, IrAF wouldn’t launch a single operation anywhere over the battlefield (not to talk deeper over Iran) without their availability. That’s how much difference were they making.

***

Bottom line: SAM-sites might be ‘complex & clumsy’. In comparison to speeds at which air power is operating, they are, de-facto, ‘fixed in position’, because much too slow. Moreover, and like the contemporary SA-2, or modern-day PAC-3s, IRIS-Ts, NASAMS etc. - systems like MIM-23B were not really ‘mobile’. Rather ‘truck-mounted (or -towed), and road-transportable’. Nevertheless, one can move them around; one can bring them very close to the battlefield – and thus one can take the enemy by surprise. ‘Simply’ through deploying them in unexpected positions. The crucial issue was, and remains, to act unpredictably: to re-deploy them frequently and not to power up radars and emit all the time – because any time the radar is powered up, the enemy can ‘snif’ it with help of his means of electronic reconnaissance… which is bringing me to the topic of the next ‘episode’ of this story, to be told in the Part 3.

(to be continued….)

Cool article again, thank you Tom! I have a hunch it might be connected to this event somehow: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/14/europe/russia-aircraft-downed-ukraine-bryansk-intl/index.html

Thanks Tom, this column is just about the most valuable thing on the internet these days.