IADS, Part 1

Hello everybody!

As mentioned few days ago, it’s about the time to discuss the topic of ‘integrated air defence systems’ (IADS’). That is: their organisation and deployment: their hows and whys. Think, or hope, that way many might find it easier to follow my reporting on what’s going on in the sky over Ukraine. Including what do I mean when talking about ‘SAM Walls’, ‘SAM Ambushes’, and ‘SAM Corridors’.

For the start, I’m going to offer a ‘classic historic example’ for the creation/establishment and build-up of an IADS: the one of Egypt during the wars between that country and Israel in period 1969-1973. While this might appear ‘unrelated to Ukraine’ - it very much is: the reason is that the fundamentals of that air war were relatively simple and remain valid until this very day; or, at least are simple to explain and to follow. Foremost: the resulting lessons are very much valid until this very day.

(Indeed: I would go as far as to say that, although their operators might not be aware of this fact, both the Russian and Ukrainian IADS’ of 2022-2024 are based on ‘lessons learned’ in Egypt (and Syria) of 1969-1973.)

Please mind: the following is a very rough summary (those who might want to read much more details might want to check books like The Arab-Israeli War of Attrition, Vol.1 or 1973: The First Nuclear War, just for example). Point is: the only thing that really changed in comparison to those days is that nowadays in Ukraine (and around it) there are ‘only’ much more powerful- and longer-ranged surface-to-air missile systems (SAMs), and far more comprehensive electronic support- and electronic warfare systems in use. And, of course, their number and sophistication are much higher.

***

Starting point of this ‘story’ is that during the June 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Israel conquered the Sinai Peninsula and reached the Suez Canal. On the ground, the Canal was the ‘frontline’ of this war. The resulting air war was dictated by intentions of both sides. After re-building its army, in 1967-1968, Egypt wanted to deploy it along the Suez Canal, with the aim of preparing a counter-offensive to recover the Sinai. Israel was aiming to prevent Egypt from doing this. The easiest way to do so was to maintain air superiority over Egypt (i.e. west of the Suez Canal) and bomb (from the air) any Egyptian army unit that attempted to deploy along the Suez Canal.

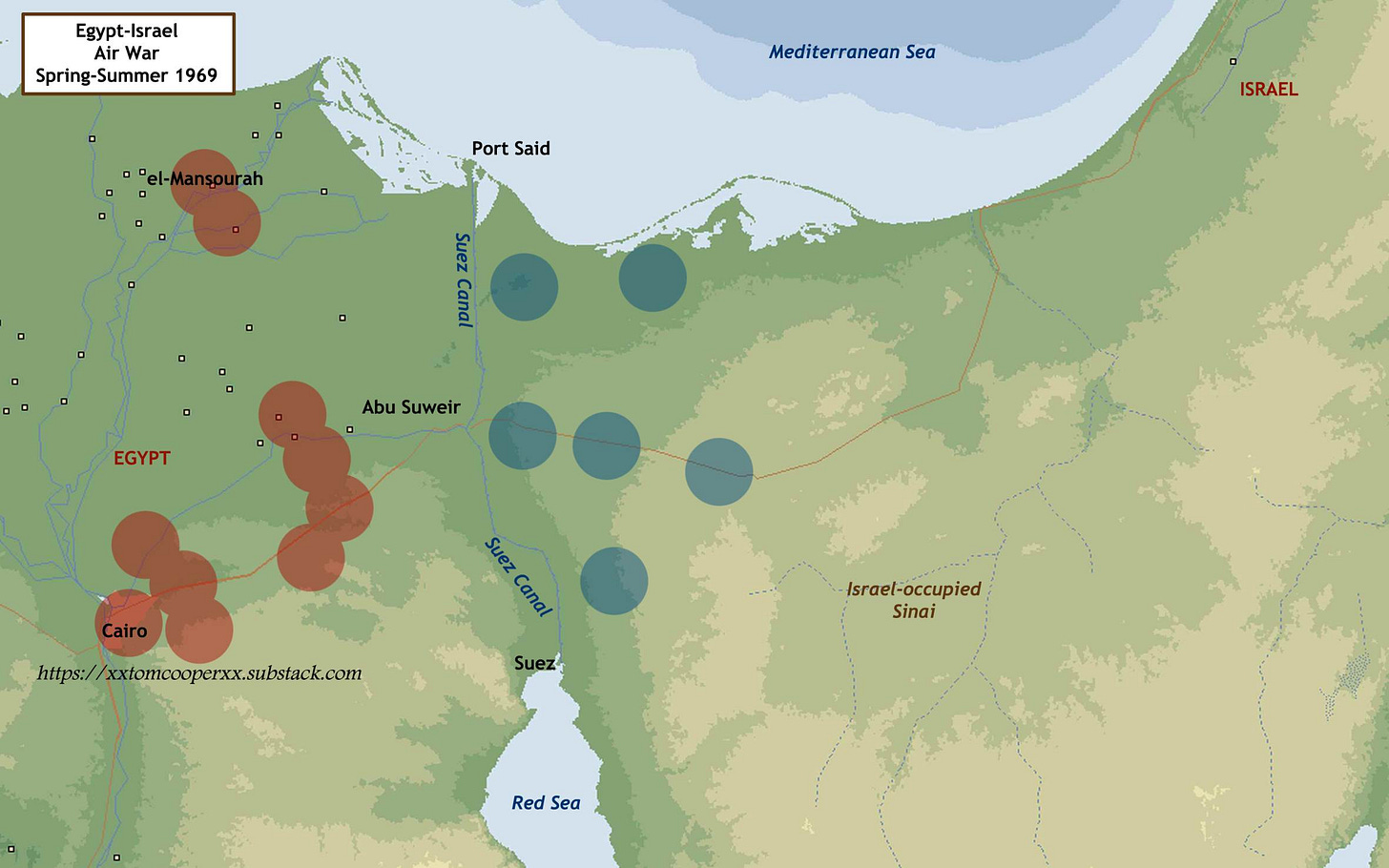

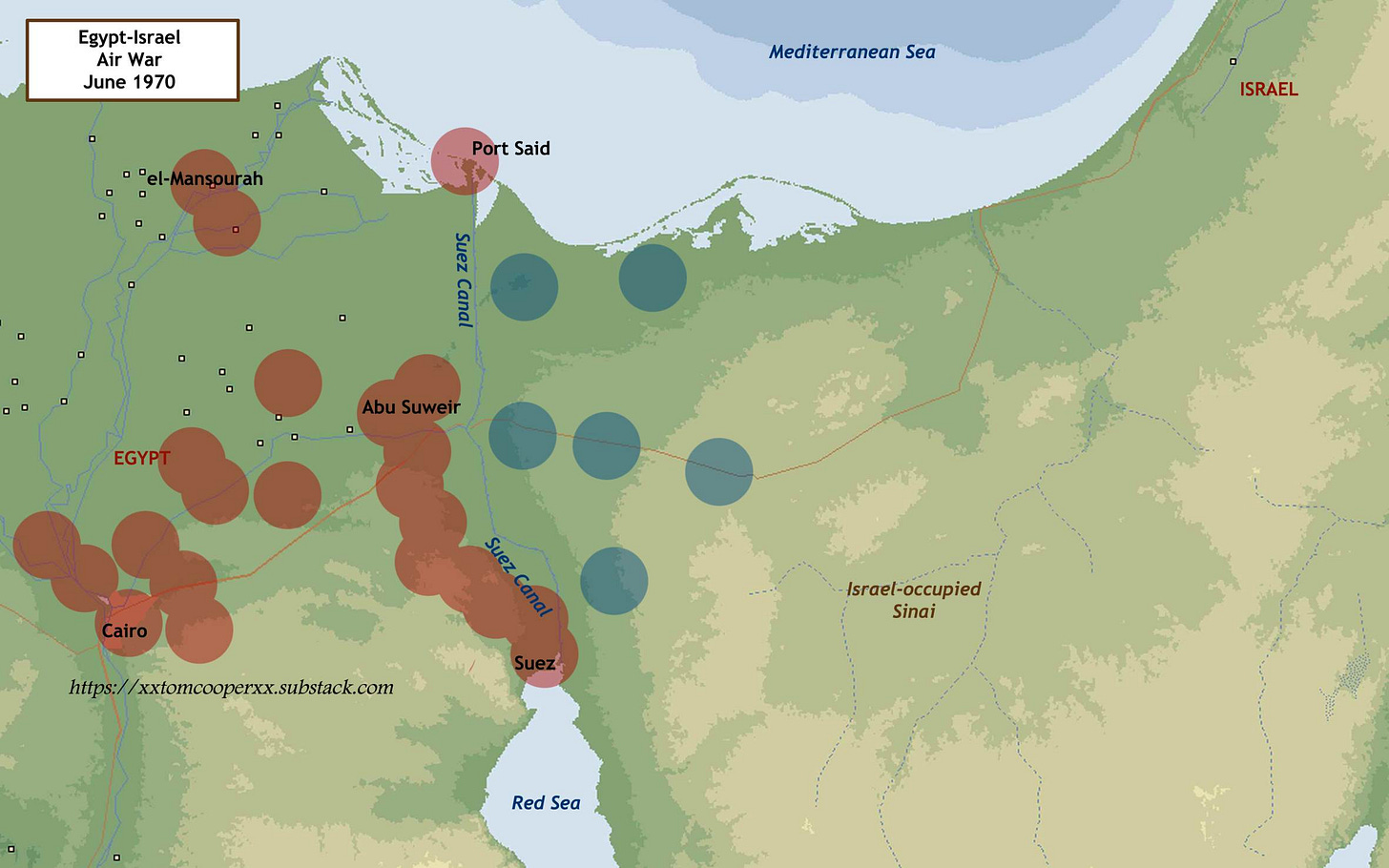

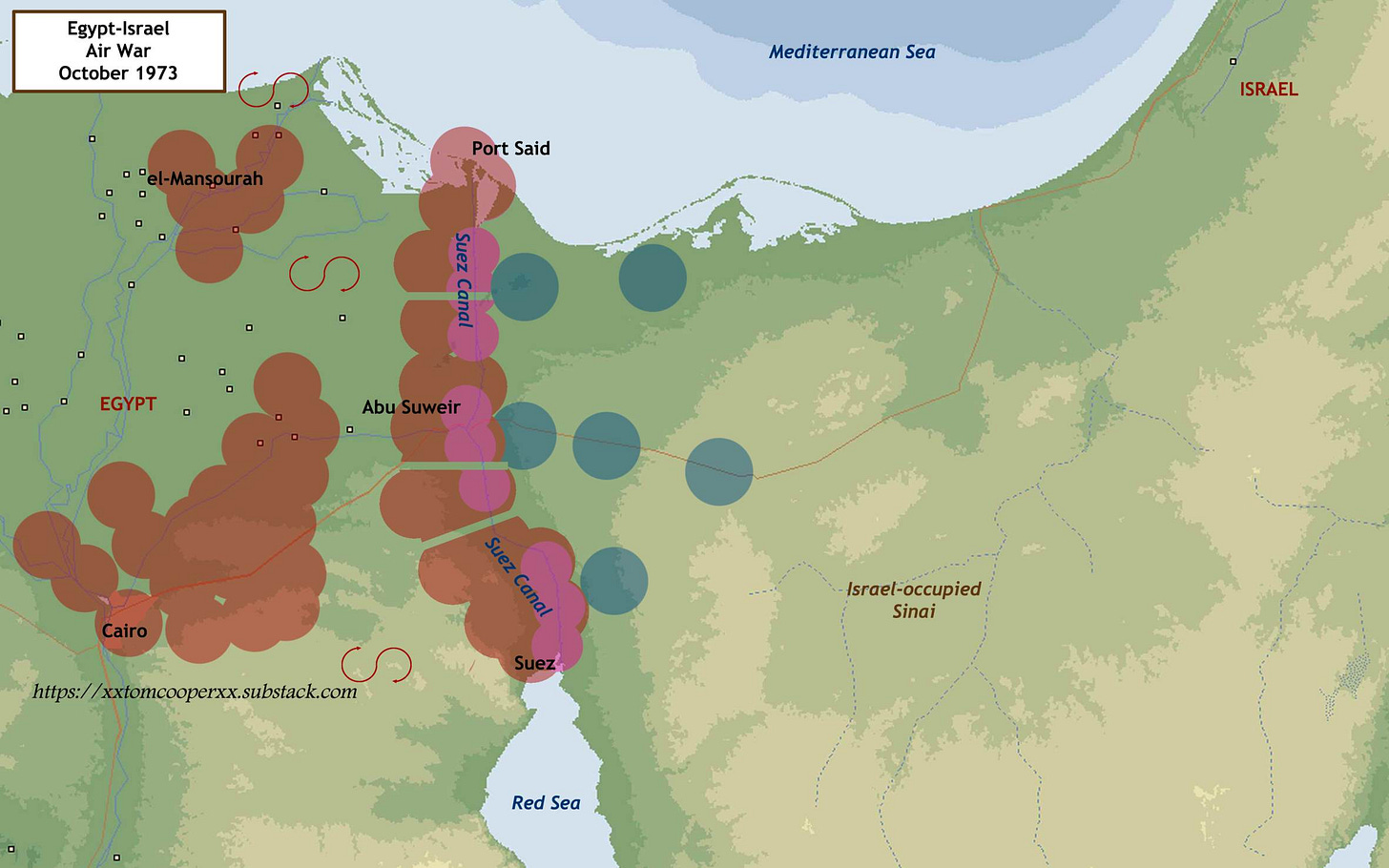

1.) The first diagram is (roughly) depicting the situation as of spring-summer 1969 (approx. March-August of that year). :

- Red circles are denoting Egyptian S-75/SA-2 SAM-sites as of that period. Essentially, these were protecting three air bases in the northern Nile Delta, several air bases north-east of Cairo, and the Egyptian capital.

- Blue circles are denoting Israeli MIM-23 HAWK SAM-sites. Essentially, these were protecting major forward bases of the Israeli forces responsible for the defence of the ‘frontline’ along the Suez Canal.

Notably: both sides were primarily deploying their SAMs for ‘point defence’ purposes. Essentially, single SAM-sites were protecting ‘very important installations’. Like air bases.

2.) Obviously, there were huge gaps in coverage in between of the SAM-sites in question. As a result, the Israelis had it easy to fly not only their fighter-bombers, but even their interceptors in between of these, and target whatever they wanted to target. Indeed, once they received IFF-interrogator technology from the USA, they became capable of sending their low-flying Mirages over Egypt to ambush Egyptian interceptors as these were taking-off from their air bases.

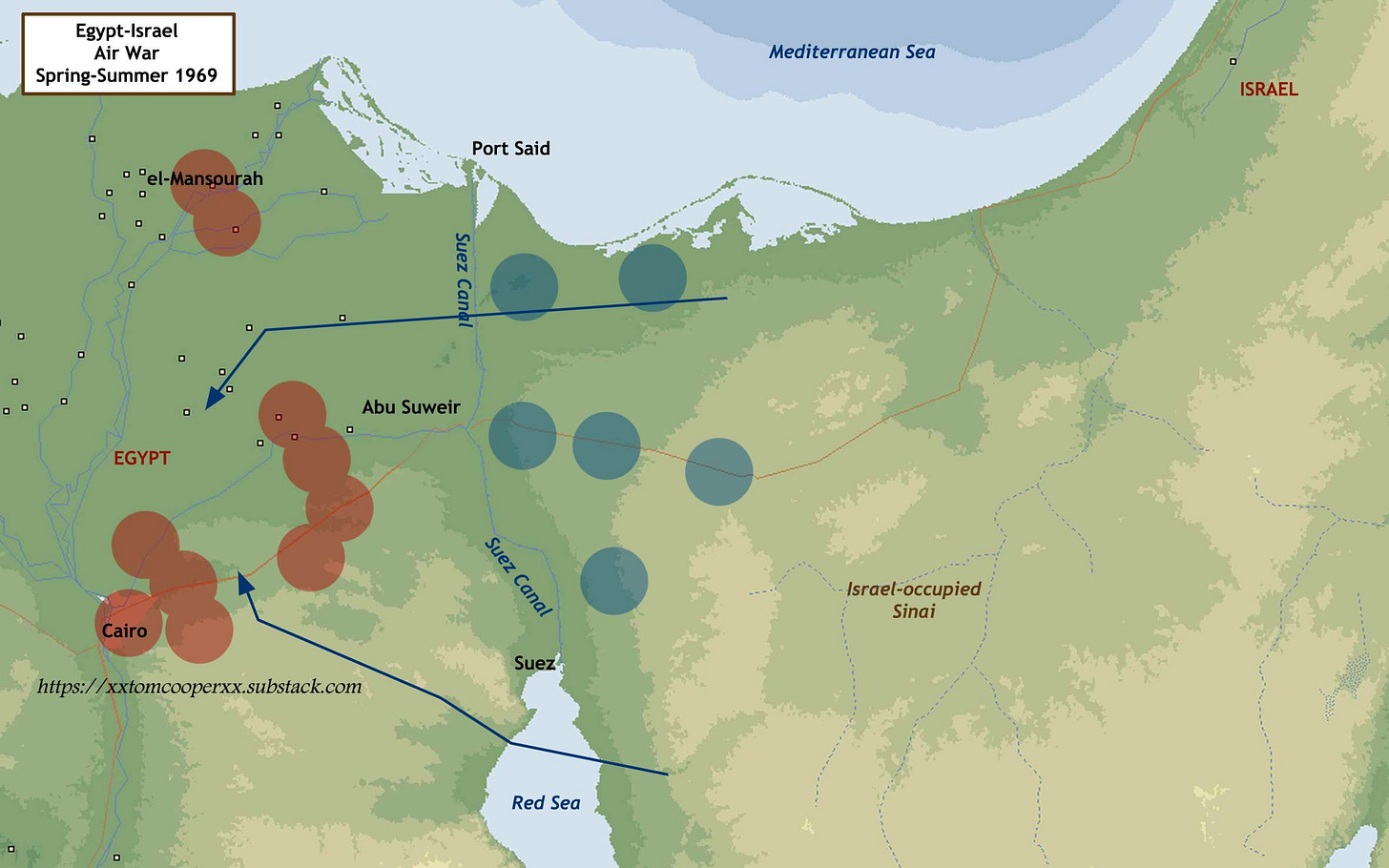

For similar reasons, the Israeli air force had it easy to bomb any Egyptian Army unit that attempted to reach positions along the Suez Canal. As a consequence, Egypt was not in position to prepare its counteroffensive. Then, in September 1969, after receiving first McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom IIs from the USA, Israel began bombing targets all the way to Cairo: some protected by SAMs, others not. The way these air strikes worked was simple: Israeli F-4Es would approach at a very low altitude and high speed (see: 15-20 metres, 1,000km/h). The Egyptian radars of Soviet design were usually unable to detect them before they were closer than about 40-45 kilometres. From that point onwards, the Egyptians had something like 2 minutes to power up their SAM-systems and scramble their MiG-21-interceptors. However, thanks to their speed, Israeli F-4Es were usually capable of reaching their targets, bombing them, and disappearing within these 2 minutes. Also because at low altitude F-4Es were faster than MiG-21-variants available to Egypt as of 1969-1970, Israeli Phantoms were usually about to re-cross the Suez Canal in eastern direction by the time Egyptian interceptors were airborne.

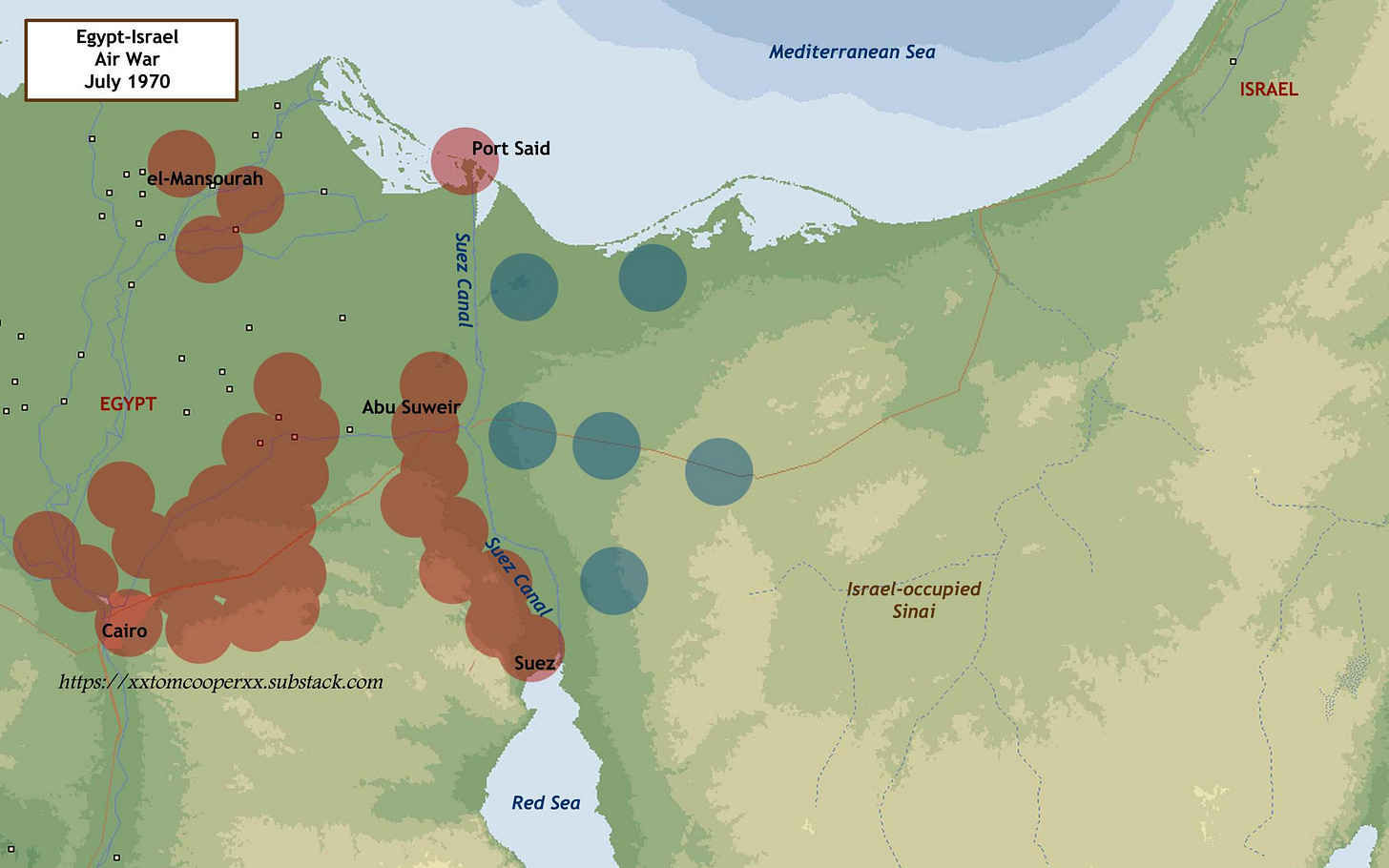

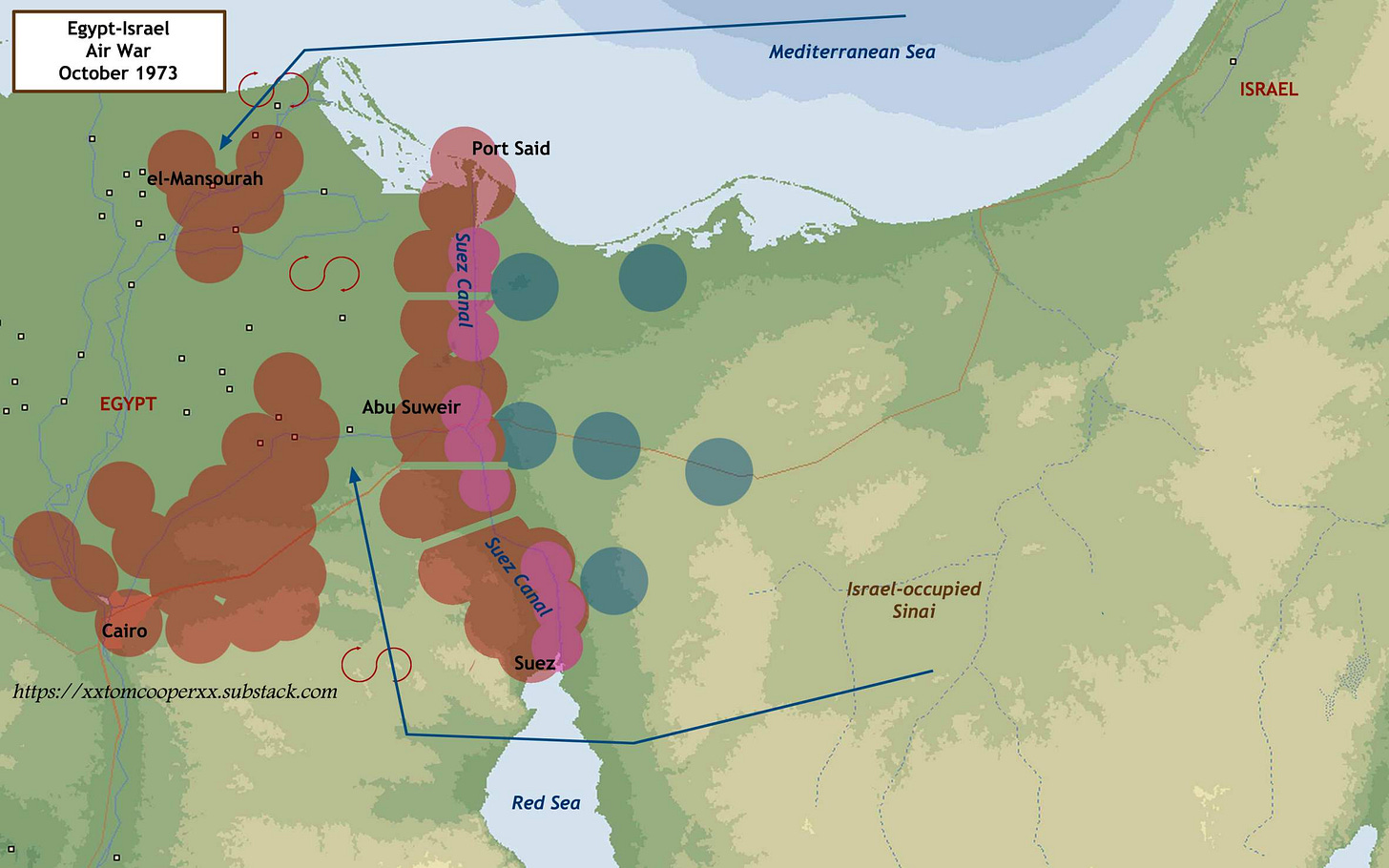

3.) Therefore, Egypt requested help from the USSR, and the USSR began delivering large number of S-75/SA-2 SAM-systems. Egypt deployed these to bolster its air defence system in overlapping fashion: essentially, SAM-sites were deployed closer to each other, to offer mutual protection. Thus, in early spring 1970, the first two ‘SAM-walls’ came into being: two of these were stretching from around the Abu Suweir Area down to the northern coast of the Suez Canal, and were positioned around 30km west of the Suez Canal – thus outside the reach of the Israeli artillery.

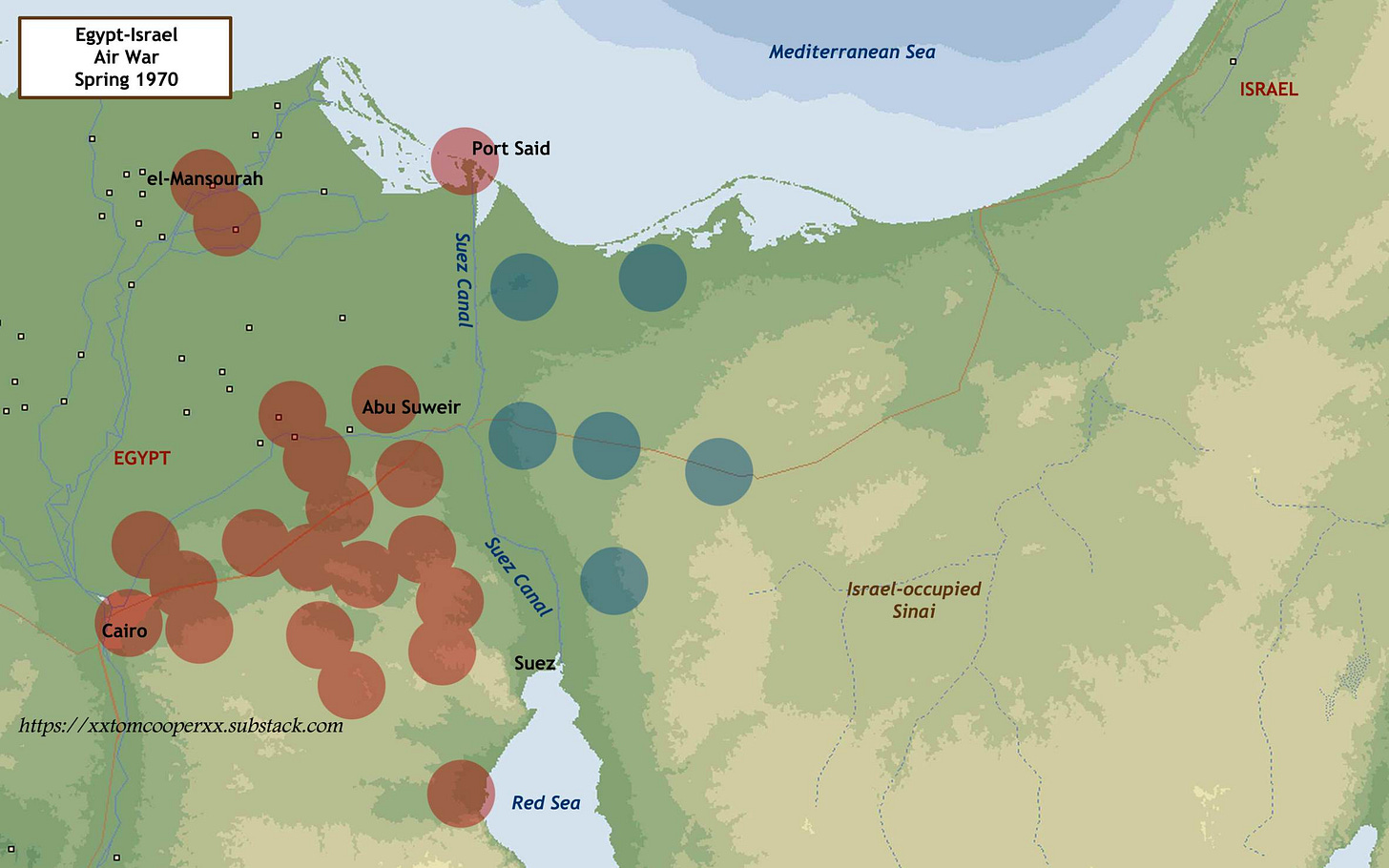

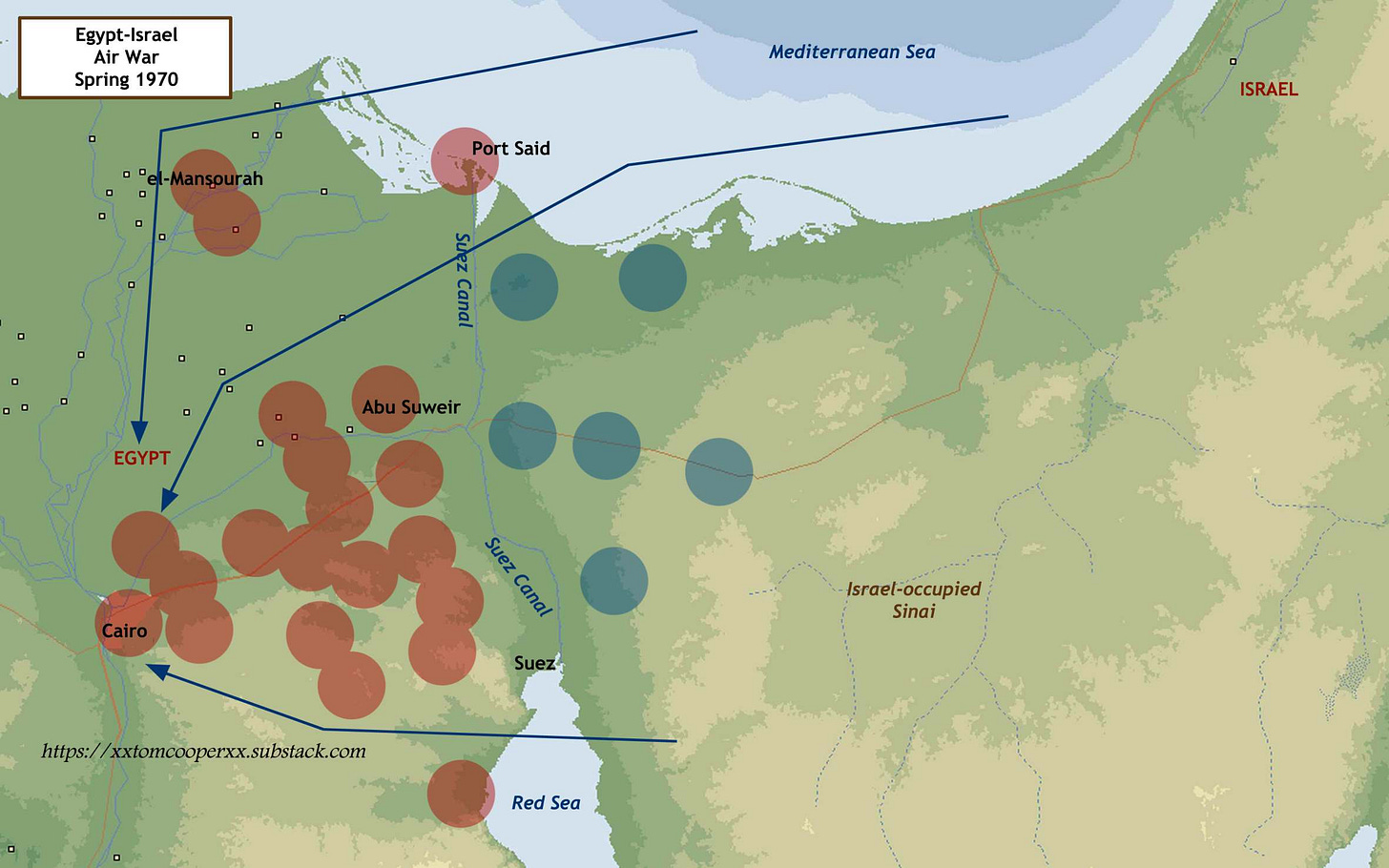

4.) Problem: there were still big gaps between SAM-sites. The Israelis still found it easy to fly ‘around the flanks’ of the SAM-walls, and strike targets in the Cairo area. Moreover, the Israelis regularly bombed Egyptian SAM-sites, thus preventing them from deployment closer to the Suez Canal. And if these couldn’t be deployed closer to the Suez Canal, so also the Egyptian Army units couldn’t deploy there (or, at most: only on temporary basis).

5.) In reaction to continuous Israeli air strikes, the Soviets then launched their military intervention and, between others, deployed their own S-125/SA-3 SAM-units in Egypt. With these in their back, in June 1970 the Egyptians began pushing their SAM-wall closer to the Suez Canal: this SAM-wall wasn’t ‘simple’ and consisting of ‘S-75/SA-2s only’ any more, but consisted of densely-interloping S-75/SA-2 and S-125/SA-3 SAM-sites, further protected by dozens of teams operating (short-range) Strela-2/SA-7 MANPADs and batteries of ZSU-23-4 Shilka self-propelled, radar-controlled anti-aircraft guns. The Israelis reacted by air strikes on SAM-sites, destroyed some, but lost a number of F-4E Phantom IIs and, eventually, gave up.

6.) Moreover, by July 1970, there were already so many S-75/SA-2 SAM-sites in Egypt, that these not only formed a ‘wall’ west of the Suez Canal, but also blocked most of approaches to the Cairo area. Late in that month, a cease-fire was arranged by the USA: along conditions of the same, the Egyptians were prohibited form deploying their SAMs closer to the Canal. However, in the final hours before the cease-fire, the Egyptians rushed so many of these towards the Canal, that – for the first time since June 1967 – they established control over the airspace over the waterway.

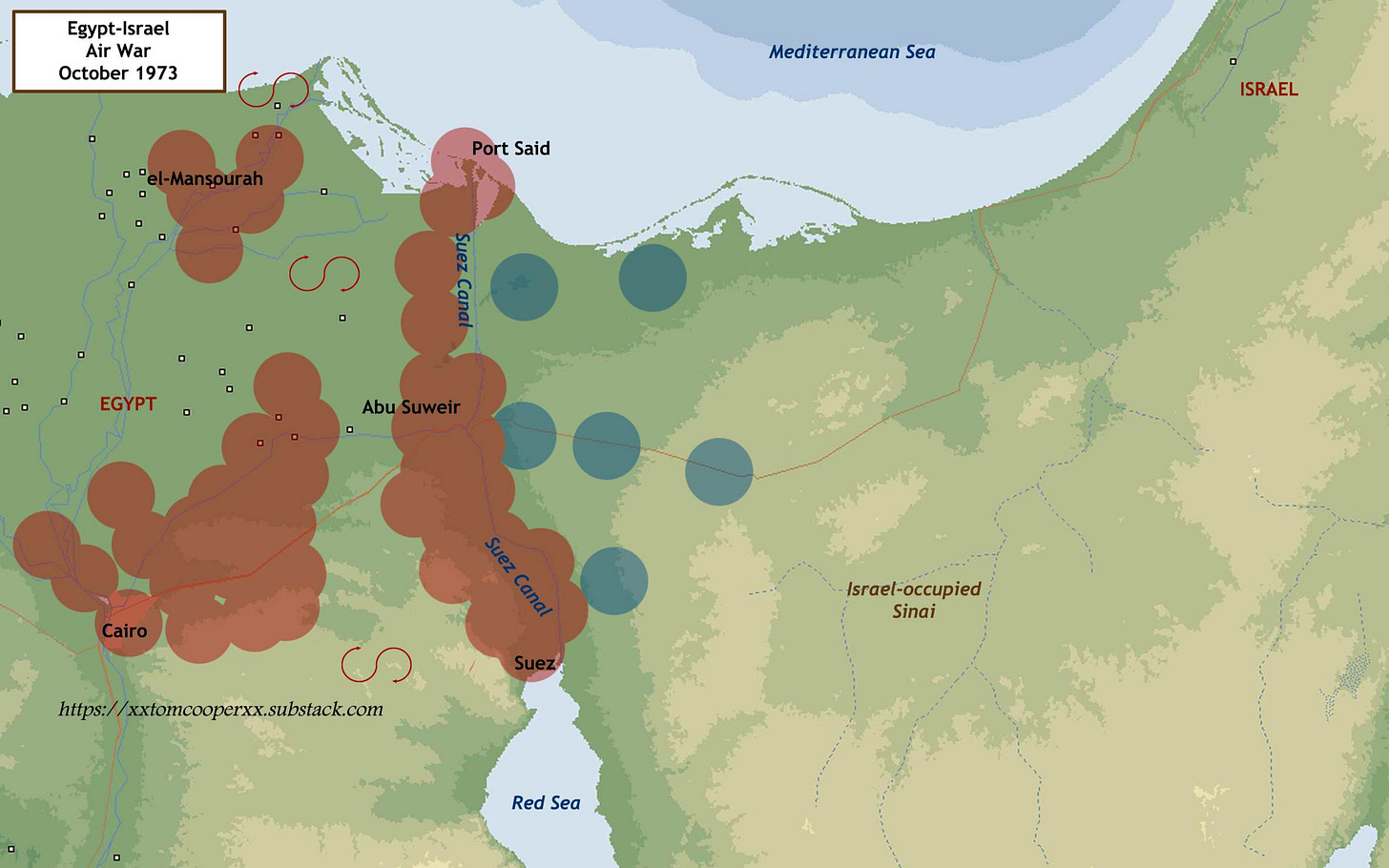

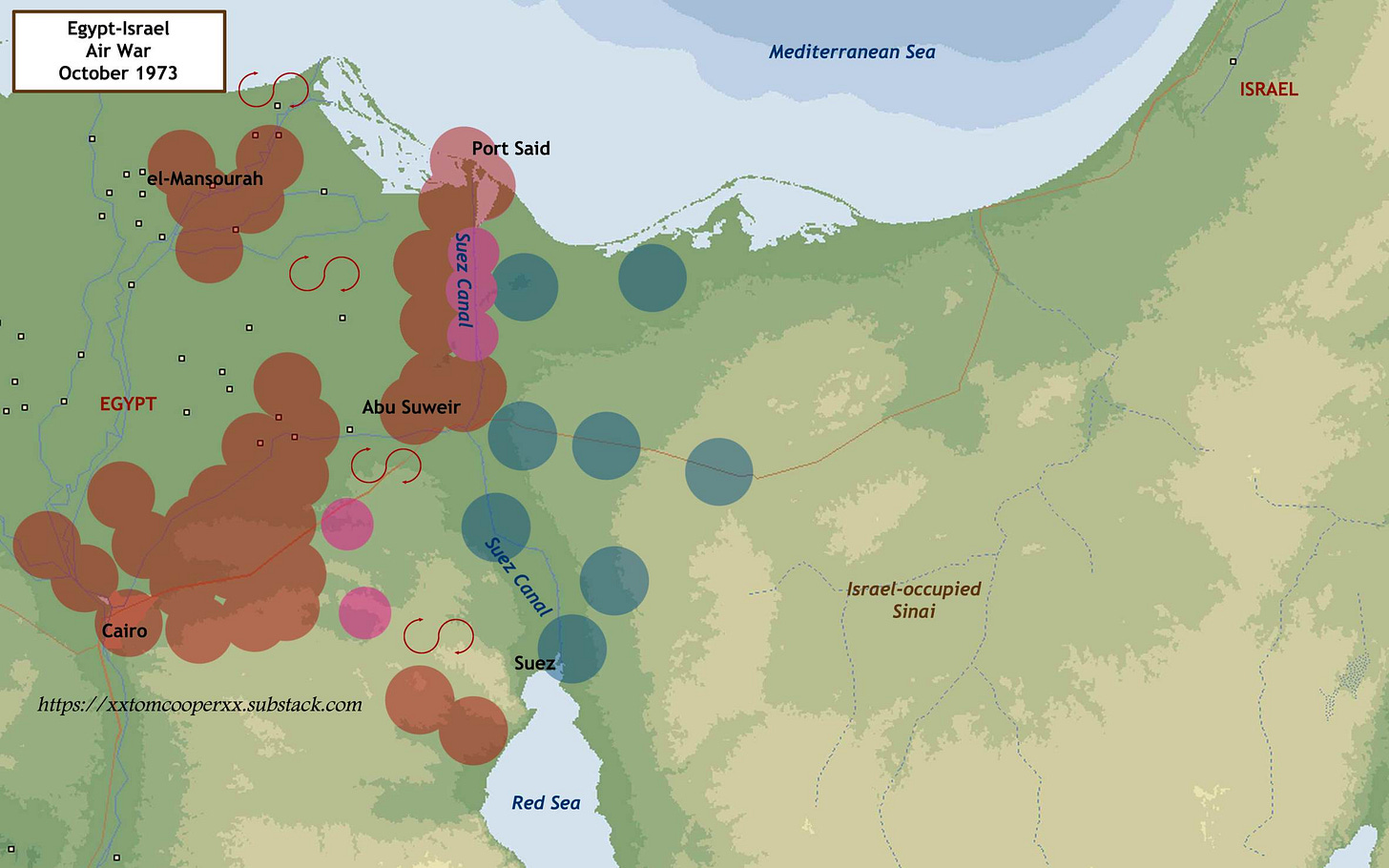

7.) In turn, this resulted in the situation over Egypt as of October 1973. By then, there was an almost continuous SAM-wall along the Suez Canal, plus one concentration of SAM-s in the el-Mansourah area, and another between Abu Suweir and Cairo.

8.) Still, in order to enable their army to actually cross the Suez Canal and assault into the Sinai, the Egyptians knew they had to protect their ground units with mobile SAM-systems. That’s why (after lots of wrangling) they convinced the Soviets to deliver mobile 2K12 Kub/SA-6 SAM-systems. The Soviets hesitated, but eventually delivered some 20 (and when they didn’t deliver more SA-6s - nor specific other goodies - as the Egyptians wanted, Sadat kicked them out of Egypt, in 1972.)

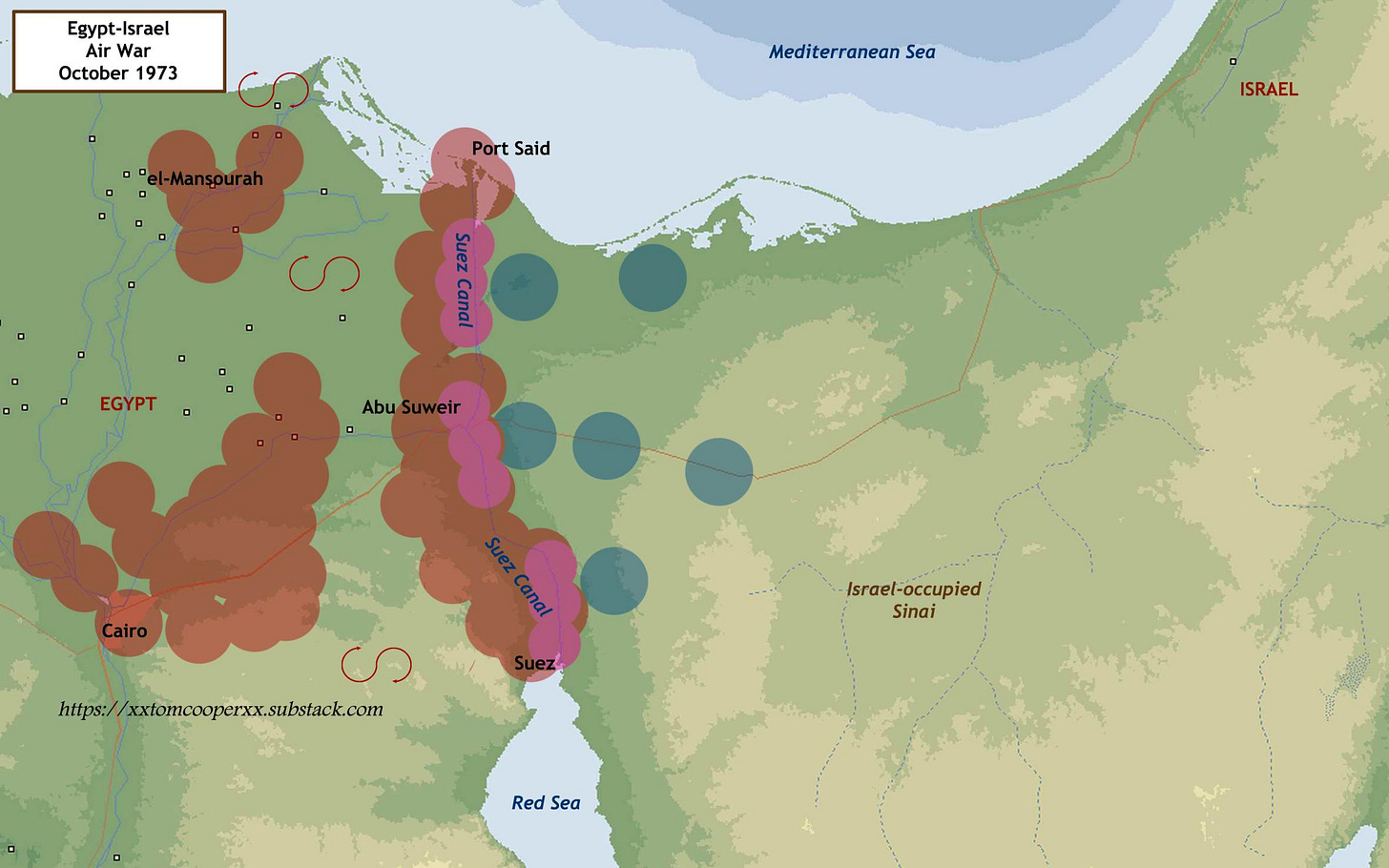

9.) That said, the arrival of SA-6s created an organisational problem for the Egyptians: precisely along the Soviet pattern, S-75/SA-2s and S-125/SA-3s were operated by their Air Defence Force (ADF; a branch separate from their air force), while their 2K12/SA-6s (purple circles on the following map) were operated by their Army. Spaces in between of the SAM-walls were patrolled by MiG-21 interceptors of the Egyptian Air Force (red ‘8s’).

10.) Because the Soviets refused to deliver the equipment necessary for their integration (so-called ‘automatic tactical management systems’, ATMS’, like Vozdukh-1/1M/1ME: this was not only very expensive, but also scarce even in the USSR), the ADF’s and the Army’s IADS were poorly coordinated with each other, and there were massive problems with their and the coordination of operations by Egyptian Air Force’s aircraft. Biggest problem was that neither the ADF nor the Army could reliably read the IFF of aircraft operated by the Egyptian Air Force. The solution was found in form of creating SAM-corridors: essentially, the air force would say the ADF and the Army something like, ‘at 06.00hrs in the morning, our jets are going to cross the Canal in West-East direction at point X, 5 minutes later, they’re going to return in East-West direction; hold your fire’. Sometimes this worked, but most of the times not: indeed, both the Army and the ADF were regularly opening fire at Egyptian and Iraqi fighter-bombers passing by (still: frequently circulated legends about ‘in October 1973 the Egyptians shot down 40+ of their own aircraft’ are within realms of science fiction).

11.) Above all, while massive, the two Egyptian IADS’ of October 1973 had another major weakness: while single SAM-sites were changing their positions every night, in grand total, they couldn’t travel at speeds comparable to the aircraft.

Correspondingly, even early during the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War - in the days it was suffering highest losses to the Egyptian (and Syrian) ground-based air defences - the Israeli air force found it easy to outflank the system: fly north or south of it, and then strike Egyptian air bases, for example.

12.) That said, during that war, the Israeli air force never really found a solution for Egyptian (and Syrian) SAMs. Sure, it launched several big operations against them (for example: it bombed those in the Port Said area for more than a week), but it continued suffering losses while doing that (something like 1 fighter-bomber for 1 SAM-site it destroyed: this was deemed ‘unacceptable’). Eventually, it was on the Israeli ground forces to (starting with 15 October 1973) cross the Suez Canal, drive around the Great Bitter Lake and then in direction of the Suez City, and destroy numerous Egyptian SAM-sites as it went. It was in this fashion that Israel created (a huge) SAM-corridor, then widened this, and established air superiority over the Egyptian Third Army (deployed along the southern section of the Suez Canal). Atop of this and to protect its bridges across the Suez, the Israeli air force then deployed two of its MIM-23 HAWK SAM-sites and numerous TCM-20 anti-aircraft guns close to the Canal.

***

Conclusion: as explained in the introduction, all these experiences are providing the fundamentals of modern-day IADS. You’ve got the Egyptians going from point-defence to dense SAM-walls, close integration of multiple SAM-sites into overlapping systems creating ‘multi-layered air defences’, and then creating two distinct IADS’. You’ve got the IFF-related problems, and the Egyptians reacting by creating (temporary) SAM-corridors through their own SAM-walls to safeguard their own fighter-bombers. You also have the Israelis learning to exploit shortcomings of single Soviet-made SAM-systems, and then finding such tactical solutions like flanking SAM-walls, before receiving US-made high-tech expected to enable them direct strikes on SAM-sites with the aim of destroying these and thus ‘drilling’ their own SAM-corridors through the Egyptian SAM-walls. Sure, in 1973, this ‘didn’t really work’, which is why it was on the ground forces to do the job of the air force, ‘instead’. However, all the elements of modern-day air warfare over Ukraine were already ‘in place’.

For comparison, the Israeli air defence system was highly-sophisticated in terms of equipment (the MIM-23 HAWK was easily outmatching S-75/SA-2 and S-125/SA-3, and better than the 2K12/SA-6), but remained much simpler in regards of doctrine and tactics. MIM-23 HAWKs were deployed for point defence purposes, while the huge areas in between were covered by Mirage III/5 and F-4E Phantom interceptors.

As next, one should keep in mind that the Egyptian aircraft depended on their IFF-interrogators for survival already while over Egypt - in order to avoid getting shot down by ADF’s and Army’s SAMs. Their Soviet-made IFF-transponders were lacking encryption: therefore, the US-supplied IFF-interrogators operated by Israel were picking them up as soon as they were turned on, usually while jets were still on the ground, at least while rolling for take-off. This enabled the Israeli ground control to scramble its interceptors on time, and then vector them to positions from which they could intercept with advantage.

While Israeli Mirage IIICJs and Mirage 5s were as fast as MiG-21s, they were more manoeuvreable and better armed. Even more so, Israeli F-4E Phantom IIs were vastly superior in terms of sensors and weaponry: a single F-4E could carry more bombs than an entire squadron of MiG-17s, and as many air-to-air missiles as four MiG-21s. And, both Mirages and F-4Es were vastly superior in terms of their flight endurance: they’ve had a longer range than any MiGs.

That is why the Israelis ‘did not need SAM-walls’. Shouldn’t mean they never run ‘SAM-ambushes’, or never operated their MIM-23s in assault mode, though. On the contrary: they were regularly operating their HAWK SAM-s in the assault mode, and also setting up SAM-ambushes. For example, on 22 October 1973, they surprised the Egyptians by forward-deploying one of their MIM-23s in the Suez City area, then sent up a demonstrative group of own fighters and, when the Egyptians sent their interceptors - took these by surprise. Arguably, MIM-23s haven’t shot down many MiG-21s at that occassion, but they caused such a chaos in the Egyptian formation, that Mirages ‘waiting’ nearby then did ambush and shot down some 5-6 MiGs.

(…to be continued…)

Many thanks Tom for this piece of History. Every Army from BC to day learn its trade researching the previous war, so isn’t out of place the comparison between Sinai

‘73 and Ukraine 2024.

Eagerly waiting next chapter.

Nice look back. I remember at the time seeing the report at the time of the shock the IAF got when they first ran into the Egyptian air defences in '73 and the problems they had overcoming them.

And on the ground the similar shcok when the Israeli armor ran into fairly well setup antitank defences.

A side bar in this is the note that it was US defence tech that enabled Israel to achieve much of its success in its victories over its opponents. Usually glossed over in accounts of the Israeli 'David' smiting its 'Goliath' enemies.

That also shows in the Israeli defence industry's focus on higher tech weaponry while relying on its allies to provide the artillery ammunition and 'dumb' bombs.