(…continued from Part 4…)

***

Equipment

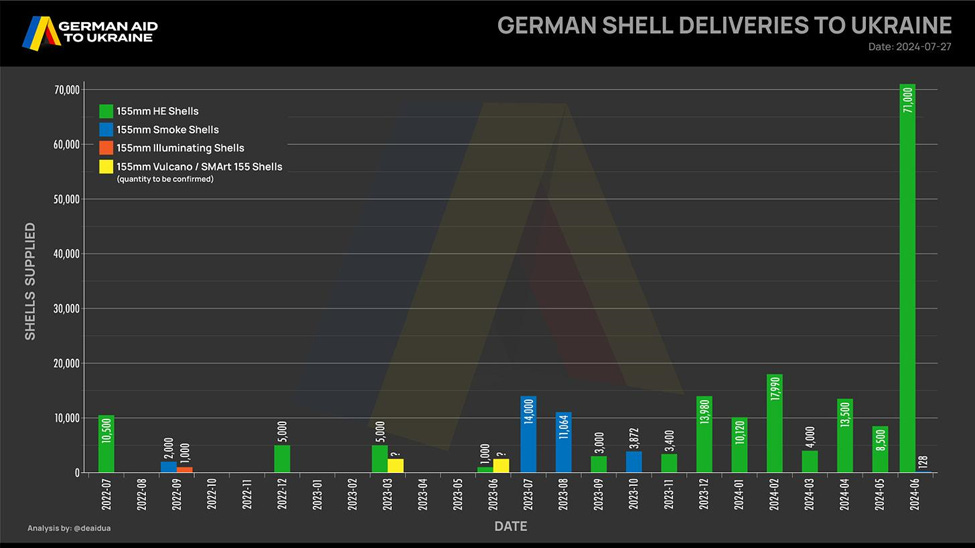

Germany’s shipment of 155mm shells to Ukraine per month. There are other sources of shells besides Germany but 71,000 shells in a month equates to 2,300 shells per day and that, by itself, is not enough. Ukraine needs 20,000 shells a day, which it’s never had. During its offensive it was firing 6,000 shells per day. A lot of new German-owned facilities are being built and ramped up so their numbers will look better in the future.

A North Korean anti-tank system was spotted in the Kharkiv region. First deployed around 2010, the wheeled vehicle carries eight anti-tank missiles with a reported range varying from 10 to 24 km. These ranges would make it a non-LOS (NLOS) missile, meaning it can attack weapons that the operator may not see. Israel has a missile that can be launched towards a direction and then acquire the target once a line of sight is obtained on approach.

A series of ground strikes by MiG-29s using Western-made guided bombs.

Drones have been dropping anti-tank mines for over a year. Many of them are recovered from Russian minefields with the fuse in the center removed so they add another fuse. They aren’t very aerodynamic making it hard to hit what you’re aiming at, but the explosion is big enough for a near miss to be effective. If you add fins it helps with the aim, and let’s make it a double while we’re at it.

Russia said they shot down a drone with a guided munition. It turns out it was a former guided munition converted into a droppable explosive but I’m sure an inexpensive drone system with a laser designator could be a future reality.

The Russians published a video showing a Ukrainian drone using remote detonation against their reconnaissance drone.

When Ukraine sunk the Moskva it used a prototype of the Neptune missile. The missile uses GPS to navigate to the target area and then uses IR to acquire and match an image loaded into memory. They increased its range to 320 km and modified it so it can attack ground targets, and they have plans to increase its range to 1000 km. A year ago the missiles hit Russian air defenses in Crimea. They’ve since taken part in attacks on Russian oil storage and refineries in Krasnodor and Port Kavkaz in the Kerch strait. Last week it struck to storage facilities for aviation weapons and machinery near Kursk, 100 km from the border. The production rate of the missile has increased “ten times'' but the original production rate was not disclosed.

When there weren’t enough armored vehicles for Russian infantry they started using a couple thousand Chinese Desertcross 1000-3, often called a golf cart. Then they started using motorcycles. Now there is an increase in the use of scooters.

***

Russian Economy

"Imagine the economy as a car. If you try to drive faster than allowed by car specifications, the engine will overheat sooner or later, and we will not be able to travel a long distance. Possibly, we will be driving fast, but for a short period. When the economy is overheated, that is, it lacks sufficient production and labor resources, the manufacture of each new item would involve increasingly more difficulties and continuously rising costs." -Russian central bank governor Elvira Nabiullina, December 2023

***

Finance ministers from eight European countries say that more can be done to enforce the sanctions on Russia but they are still hurting Russia’s economy.

Russia has struggled to suppress inflation with high interest rates but that stifles economic growth.

Factories are operating at maximum capacity. Military production is 50% higher than it was at the beginning of 2022, and Russia is spending 9% of its GDP on defense, a level it hasn’t seen since the days of the Soviet Union. But it is creating economic imbalances and erodes longer term growth. Directing restricted imports to military production creates shortages in other sectors. Civilian demand is higher than production, which increased prices and pushed inflation to 8% and the cost of everyday goods is up 19%. Labor shortages result in higher pay. The higher costs and pay results in a lower value for the ruble and higher inflation. To counter inflation, the central bank increased its interest rate to 18%, the sixth hike in just over a year. This makes it harder, or impossible, for businesses to borrow money and create more businesses or higher production.

Russian unemployment fell to a record low 2.4% as a result of conscription, casualties and emigration. Low unemployment means higher pay for workers, an inflationary pressure, and increasing labor shortages. The shortages are countered, in part, with longer work hours.

There is a shortage of one million people in Russia’s labor market. 500,000 fled the country, 300,000 were mobilized and 30,000 are recruited each month for the army, fewer foreigners are arriving for work and those that are here are considering leaving. Many young men are avoiding legal jobs where they can be identified and then conscripted. Factory workers at one plant were told they were immune from conscription but then the regime told the owners they had to remove the exemption from 20% of their workers. Labor shortages often result in higher wages, and many workers enjoy bonuses and higher pay, but the military factories have 12-hour, six-day work weeks. 14-18 year-old child employment has increased by 60-70%, 24-36 hours, and in Tartarstan they can work in hazardous industries. Low motivation ranges from 34 to 67% for certain categories of workers, which continues to be a factor in reducing labor productivity, especially in the service sector. Up to 100,000 prisoners are allowed to work for 25% of normal pay. A future mobilization can have a serious impact on production.

Russia’s foreign currency reserves are reduced by half since 2022. Russian export revenues are about a third lower, contributing to the lower currency reserves. Russia’s supply of gasoline was low enough to ban exports and then Ukraine started to attack the refineries that turn oil into gas. Starting last May, sugar exports are only allowed to Russia’s four economic union partners in limited quantities. The capital controls, export bans and heavy investments in the war industry are a return to a Soviet-style economy.

***

As Ivan Mikloš reads it: Myths and facts about the Russian economy

[Ivan Mikloš is the former Finance Minister of Slovakia and Consultant to Ukraine]

Since the beginning of Russia's war against Ukraine, observers, as well as the public, have been most focused on developments on the battlefield, which is natural and understandable. However, economic development is also very important, because without a functioning economy, not only military victory is not possible, but also simple survival.

Many economists, including the author of these lines, thought that Western sanctions would have a rapid and devastating effect on the Russian economy, but this did not happen. I have already written several times about the reasons and context of the failure to meet these forecasts, but also about the falsity of the arguments about the complete ineffectiveness of sanctions.

At this point, I will only add that one of the weakest points of anti-Russian Western sanctions is their insufficient enforcement, especially tolerance of their circumvention by third countries and their companies. This is best illustrated by the multiple growth of imports to Central Asian countries from EU countries since the beginning of the war, and at the same time the equally high growth of exports from these countries to Russia.

Turkey is also a very good example. In early February 2023, the EU imposed an embargo on imports of Russian petroleum products. During the year of this embargo, until February 2024, Turkey increased its imports of petroleum products from Russia by 105 percent and at the same time its exports of these goods to the EU by 107 percent. On this Turkish re-export alone, Russia earned more than $3 billion a year.

The US is much more effective in enforcing compliance with sanctions. They are helped by the threat of secondary sanctions against any entity that trades in dollars. This instrument is already causing macroeconomic damage to Russia.

Nevertheless, there are still more and more reports of positive developments, especially high economic growth, and these reports are proclaimed by Russian propaganda, as well as by its foreign disseminators, as evidence not only of the ineffectiveness of sanctions, but also of the hopelessness of the Ukrainian fight against the Russian aggressor.

At the same time, the reports about the high growth of the Russian economy are true. Last year, it grew by 3.6 percent and in the first quarter of this year it even achieved a year-on-year growth of 5.4 percent, which led all international financial institutions to increase this year's expected economic growth (the range of their estimates increased from 1-2.2 percent to 2.5-2.9 percent).

But this high growth is neither healthy nor sustainable, and this is not only said by independent Western analysts, but also by official Russian expert institutions. For example, the Institute of National Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences* estimates that growth of 5.4 percent (in the first quarter of 2024) significantly exceeds the potential growth, which they estimate at 3 percent, a maximum of 3.5 percent. Russia has switched to a war economy that is significantly overheated and is growing mainly due to rapid growth in public spending (year-on-year growth of 21.5 percent in the first four months of this year), thanks to growth in military spending (9 percent of GDP), rising salaries and growing domestic consumption. Domestic consumption is being boosted by social and military benefits, and wages are being pushed up by acute labor shortages, largely as nearly a million men flee to mobilization abroad and hundreds of thousands more have been drafted into the military.

The main problem with such growth is its unsustainability, while the fundamental problem is rising inflation, which must be neutralized by a very restrictive monetary policy. This is confirmed by the central bank itself, whose respected governor Eľvira Nabiullina published a text in June in which she warns of an increasingly likely scenario of a further rise in inflation and a possible subsequent increase in the key interest rate in July.

Nabiullina sees four risks – overheating of the economy, labor shortages, rising inflation expectations and geopolitical factors, i.e. sanctions. The Governor speaks about these risks relatively cautiously, but clearly, while it is evident that they are all coming true and the chance that they would diminish or even disappear is minimal. And there is another serious problem. According to the central bank, the volume of Russian imports has recently decreased as a result of secondary (especially American) sanctions, which has an inflationary effect, as it reduces aggregate supply, which is countered by ever-growing aggregate demand. Although high interest rates do not translate into lower consumption (i.e. do not reduce inflation), they negatively affect investment and business activity, and thus threaten growth dynamics in the medium term.

So Nabiullina, who has been harshly criticized by the business sector for her restrictive monetary policy, but also by some propagandists, makes no secret of the fact that there may be a further increase in the base interest rate in July. He literally writes: "... We also consider a substantial increase in the base interest rate in July to be possible. Monetary conditions will remain tight for as long as it takes to bring inflation back down to the target." Let us add that the target is at the level of 4 percent, while the current inflation is at around 8 percent and the assumptions for its reduction are minimal.

To understand why such high interest rates (and even the prospect of raising them further) are such a big problem, it is enough to compare them with Ukraine and the level of the Ukrainian base interest rate. Before the war, in 2020-2021, both countries had a base interest rate at a similar level of around 6 percent. After Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the Russian central bank prevented a monetary collapse by, among other things, raising the base rate to 20 percent, but already in September 2022, this rate was at 7.5 percent, mainly thanks to record foreign exchange earnings from oil and gas exports, while the Ukrainian base rate was 25 percent at the time. But where are we today? While Ukraine is constantly lowering its base rate, and the last time it happened in June was from 13.5 percent to 13 percent, in Russia the base interest rate has been at 16 percent since the end of last year and may increase even more in July. [It’s 18% now].

Interestingly, while Nabiullina (as well as forecasters from the Russian Academy of Sciences*) do not see the prospects for an overheated Russian war economy very positively, ordinary Russians see it much more optimistically.

According to a survey by the Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, concerns about future economic developments have weakened in Russia over the course of 2024, and fear of the consequences of economic sanctions has approached the minimum level measured over the past two years.

Well, let's see if the experts or the propaganda-massaged public are right.

***

* This next report might be more closely related to the Russian economy than general Russian news because Valentina Bondarenko was a top economist. She died last week at the age of 82. She’d worked at the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy since 1988, and was appointed director of the economic research organization, the International N.D. Kondratiev Foundation in 1993, a position she held until her death on Monday. The list of those who fell out of windows may not be as long as you think, but Valentina is now part of that list. It’s speculation as to why any of them died such a public death, and Tass informs us that emergency services say that Bondarenko's "death is not of a criminal nature, the woman had been ill for a long time." I don’t know why illness is an explanation for falling out a window. I have no idea what information she might have known as the director of economic research. I do know that Putin is the leader of her country.

Dear Don, thank you for reports! Detailed, insightful, produced with care.

I would like to comment on economy side, those economists predicting quick downfall after sanctions are like generals predicting fall of UA army in two weeks.

Economy is very much like human body, means it is vulnerable, but much more resilient then we used to think. And the key is "quick collapse". If it has not happened then nothing would happen further, means when changes are slow, people get used to it. And there is quite a way to go to soviet style economy. It could take decades of slow degradation.

So even looking from that angle of economy alone is distracting. What economists might do instead is to look for ways to impact military production, how to make it less effective, how to disrupt production chains. Then those sanctions might be useful. There is a lot there, means military production network is not homogeneous, some aspects are more impactful then other, and some may give critical leverage.

Hah, it's *exactly* that public sentiment which goes "hey, wages are going up because labor is scarce, I'll have money forever" that drives an unstoppable wage-price spiral. Putin is sacrificing stability tomorrow to extend an unwinnable war today. Brilliant strategic choice.

What's so hilarious about the US terror of russia collapsing if it loses in Ukraine is that the thing is doomed in the long run as it is. Just like Americans would be better off if D.C. went up in smoke tomorrow, about the only thing that can save russia now is the razing of Moscow.

Wagner had the right idea - too bad they chickened out.