Withdrawal Operations, Part 2

(…continued from Part 1…)

Delay Operations

A delay operation has many of the same characteristics of a withdrawal operation but the objective is different. In a withdrawal, the force is trying to disengage from the enemy. A delaying force remains engaged with the enemy but trades space for time. It avoids a decisive engagement but tries to maximize the destruction of enemy forces. A delaying force can be a covering force for a withdrawal, it can be a force that is inadequate for a defense, or it can be an economy-of-force operation in which a commander chooses to be weak in one sector so he can mass forces in another sector.

***

Retirement Operations

A withdrawal operation can become a retirement operation once the force is disengaged from the enemy. Columns can then be formed for faster road movement.

***

Historical Operations

Here are some historical examples of withdrawals. Take note of the planning:

● Security Forces (Observing the enemy, denying enemy observation, and providing defenses for withdrawing units)

● Mobility (Retain organized movement through control measures. Reduce enemy movement by direct/indirect fires, engineering obstacles such as mines, and terrain)

● Deception (Deny enemy knowledge to achieve surprise. Generate false impressions through feints and other activities. Create indecision for the enemy)

● Conservation of Combat Power (Withdraw less mobile units first. Use mobile units in the security force. Use the fewest amount of troops in the security force that will still accomplish the mission)

The Dunkirk Withdrawal Operation

In late May 1940, during the Second World War, German forces trapped French, British and Belgian forces along the English Channel. The Channel was a terrain obstacle for allied movement that was partially mitigated by the Allied naval force and civilian naval craft. Some of the allied forces provided security as a delaying force by manning the defensive perimeter against the advancing German forces. Other forces withdrew to the beaches and harbors to await transport to England. After 338,000 allied soldiers were evacuated, the operation was concluded due to the increasing cost to the naval and air forces. The same water object that hindered allied movement prevented German forces from crossing into England, but it also prevented the security forces from escaping. For every seven soldiers that were evacuated, one was taken prisoner.

***

The Wolfhound Regimental Delaying Operation

In the opening days of the Korean war, US troops on occupation duty in Japan were poorly trained, just five years after World War 2. When confronted by North Korean troops, the Americans alternately fought hard or ran away. This continued for three months before they gained their footing, after which they performed well. There were two exceptions to the initial erratic performances. The Marine’s 5th Regiment arrived from California ready to fight and later became the 1st Provisional Brigade. The other unit was the 27th Regiment of the 25th Division, which was nicknamed the Wolfhounds. For some reason, they had excellent and knowledgeable leadership in both the officer and non-commissioned ranks and the enlisted soldiers followed them with confidence.

At this time, the UN forces were in general retreat and the 27th regiment was asked to hold off the advance of a North Korean division. The Wolfhounds delaying operations were always organized and effective, holding back the more numerous North Koreans until their position became untenable, and then they withdrew to the next position. They were aided by the terrain and their planning.

The route they were blocking was a road in a narrow valley flanked by rough hills that were covered by trees. By deploying across the road, the US regiment forced the North Korean division to move out of a column formation in order to engage them. With dug-in positions that had good fields of fire that supported each other, US direct and indirect fires took a toll on the North Koreans.

It would usually take about 2-3 days for the North Korean division to find the flanks of the US regiment and threaten to turn them. During that time, the regimental staff had been scouting and developing the next positions to defend. These positions were dug out and the company executive officers, first sergeants and platoons sergeants were shown the route they would take during the next withdrawal. The locations of the headquarters, artillery and logistical units were also identified. When the decision was made to pull back, the main force did so along the rehearsed routes while the security force held off the enemy forces. When the main force was in their new defensive positions, the security forces pulled back under the covering fire of artillery.

The Wolfhounds conducted these delaying operations for a couple of weeks, trading land for time and the North Korean division suffered heavy casualties. When the UN made their stand at the Pusan perimeter, the Wolfhounds and the provisional Marine brigade were used as fire brigades and sent wherever the North Koreans were threatening to break through.

***

The Kherson Withdrawal Operation

In September, 2022, Ukraine launched its Kharkiv offensive. Over at Kherson, Russia had 30,000 troops north of the Dnieper. They had been supplied across three bridges, but the Antonivka railroad and road bridges were heavily damaged in August, and by September 3rd, the bridge across the Nova Kakhovka dam was made impassable. Russia tried to establish a pontoon bridge underneath the damaged Antonikva road bridge but it was repeatedly damaged. They finally established three ferry crossings in the Nova Kakhovka area and two near the Antonikva road bridge.

The Russian supply situation was tenuous with three bridges and it was even more endangered when they had to rely on five ferry crossings. The Dnieper river usually, but not always, freezes between January 3rd and March 3rd. If it did freeze the ferry operations would end. A Ukrainian general said the Russians would have to withdraw by the end of November. Withdrawal operations should happen before the situation deteriorates. The Russians recognized the inevitable and started planning the withdrawal in September and began executing it in October. The larger headquarters, intelligence units and support units were withdrawn first and by October 20th, the movement of units was noticed by the press.

The control measure that Russia used was a timetable that listed when each unit would withdraw. That was easy enough for units that were not on the front line but if Ukraine launched an attack as Russian units tried to withdraw they could potentially pin units down that were supposed to withdraw, and they might break through where units were supposed to stand and fight. There was a high probability that their security force fighting a rearguard action would be trapped on the right bank of the river with Ukrainian artillery firing on all the crossing points. If things went really poorly for Russia, a lot of men and equipment would be lost.

But that didn’t happen.

Russia moved artillery units to the left bank where they could provide fire support for much of the withdrawal. They extensively mined and boobytrapped roads. Then they pulled out their Spetsnaz and airborne units that they wanted to preserve. Finally, they pulled their regular and separatist units out, destroying bridges behind them.

Drones had been used since the beginning of the war, but at that time there were very few of them and they were a lot more expensive. Russian air defense units were part of the plan to reduce Ukrainian drone activity and this denied Ukraine a timely view into a quickly moving situation.

Ukrainian forces moved forward cautiously when they were sure Russian positions were vacated, clearing the mines in front of them, but they didn’t pursue or engage the withdrawing Russian units. Publicly, they were worried about Russian deception and luring them into a fight in Kherson’s urban environment. “It’s important to understand: No one leaves any place just like that,” said Zelensky.

So the Russians withdrew behind their artillery umbrella operating on the left bank, placing even more mines as units were being ferried across the river. The embarkation and landing sites for the ferries were not attacked with artillery or HIMARS rockets and the last of the Russian security forces were able to cross intact. In a final act, Russian engineers completely demolished the three heavily damaged bridges across the Dnieper. With that, the potential to kill or capture 20,000 or more vulnerable Russian troops with their associated equipment had passed.

***

The Avdiivka Withdrawal Operation

The city had been on the front line for ten years with the 110th Mechanized Brigade being the primary defender for the last two years. With Ukraine’s summer offensive winding down in October, Russia decided to target it with 40,000 troops, probably because it was already surrounded on three sides. Russia suffered tremendous losses from Ukrainian artillery and drones and managed to advance 2500 meters in the north towards Stepove, but the lines remained fairly static from the end of October until January. By January, the interruption of US aid resulted in increasing shortages of artillery shells, making defensive operations more difficult.

In mid-January, Russians moved through a sewer line and emerged in the southern part of the city. At the beginning of February, the Russians had a breakthrough by the dachas in the north, aided by the fog and nighttime attacks. Drones had been trying to fill the void that was left by the absence of artillery fire but they couldn’t fly if they couldn’t see, and some Russian attackers were using thermal ponchos that obscured their heat signature from drones with thermal cameras. Without effective artillery or drone support, the Russian attackers overwhelmed the defenders and quickly pushed two kilometers through the dachas and into the city.

Smelling blood, Russia began pouring troops into the battle and intensifying their artillery and airstrikes. Already being hit by 20 airstrikes a day, the attacks on Ukrainian positions increased to over 50 a day. Artillery, MLRS, thermobaric and incendiary magnesium shells were also used. Some of the 110th Brigades units were at 50-70% strength and they had no artillery to help in their defense, let alone counter attacks. It was past time to withdraw.

A week after the breakthrough in the north, Syrsky was named the new commander of the army. Zelensky publicly said that he asked Syrsky to defend the city and the 3rd Assault Brigade was brought in as reinforcements. They were known for their methodical 10 kilometer advance south of Bakhmut but they weren’t there to reestablish the defensive perimeter, they were there to help the 110th Brigade escape the city. Zelensky’s statement was simply an attempt at deception.

It was not the entire 3rd Brigade that was sent: merely one (large) battalion. Even though the brigade would be outnumbered 7:1, increased troop density would result in more casualties from the intense Russian artillery and air strikes. For many, it would be their first experience in combat. The unit’s junior leaders would need to control the rapidly changing battlefield even if they lost communication with their senior leaders. The front line infantry, especially the inexperienced ones, would have to trust their leadership.

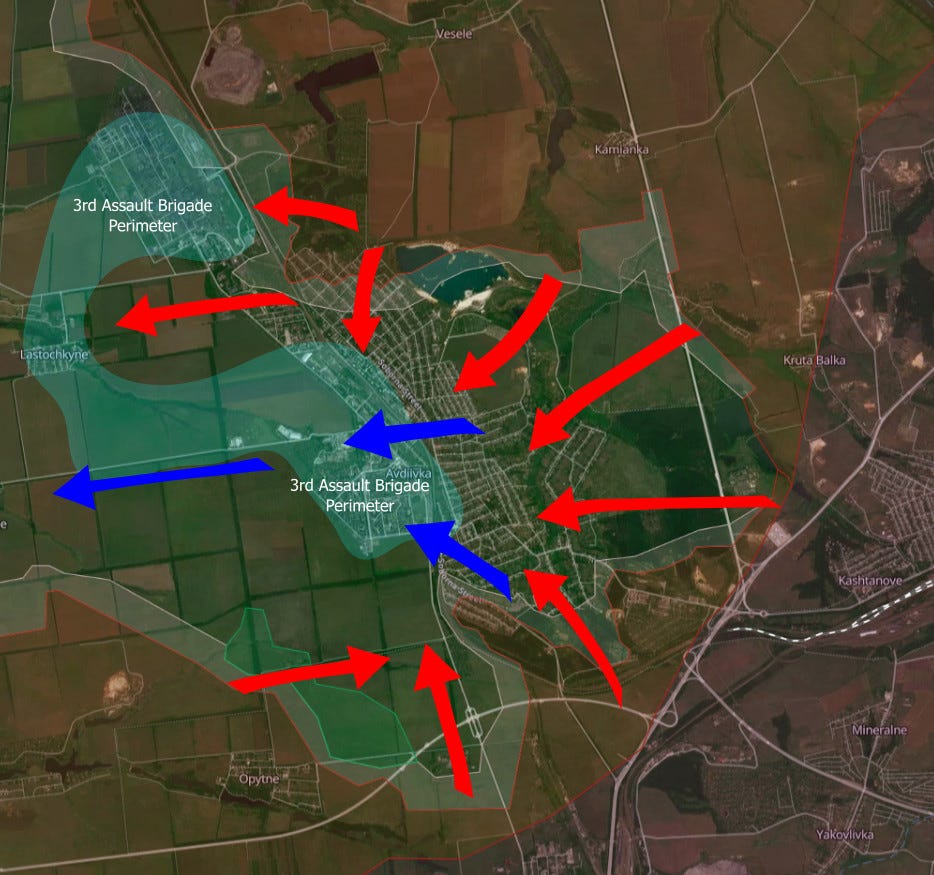

The 3rd was given overall command of the city and was assigned the 225th Independent Assault Battalion, the special forces Timur Group and the Russian Volunteer Group as reserve forces and to strengthen the perimeter outside the city. The plan was for the 3rd to establish a defensive perimeter on the western side of the city and hold the line while the 110th withdrew units first from the far eastern defenses, and then the units from the closer southern defenses. There was a company-sized unit in the isolated southern strongpoint of Zenit that was tasked with holding out until most of the 110th had withdrawn in order to prevent a stronger Russian advance from the south.

Withdrawals are best covered by heavy artillery fire to slow down the enemy and prevent their pursuit. In the absence of artillery fire, Ukrainian forces would rely on the supply of 120mm mortar ammo that the 3rd brought with them as well as their drones. Ukrainian forces would depart by the northern road by the coke plant and by the southern road, which was closer to most of the troops of the 110th Brigade.

The order for the 110th Brigade to begin the withdrawal was given by radio and almost all the personnel received and acted on it. A few isolated troops did not hear the order began their retreat only after realizing that they were behind enemy lines.

The 3rd Brigade was heavily outnumbered. Artillery and airstrikes aimed at them also killed Russians that were in nearby buildings or the same buildings as them. Eventually, the Russians achieved a breakthrough and seized the northern road up to the outskirts of Lastochkyne village, where 3rd Brigade troops held the line. Inside the coke plant, the command center organized the defenses and planned fall back positions and withdrawal routes.

A couple of days later, they were about the withdraw at their assigned time when soldiers from a battalion of the Presidential Brigade ran into their position. They had been fighting alongside the 110th Brigade over the last couple years but half of their unit lost contact with their command and the other half of their unit. The 3rd Brigade troops postponed their withdrawal until all of the troops from that unit evacuated, even though every minute they delayed increased the danger they were in. When they finally began to withdraw themselves and the Russians realized it, the Russians increased their attacks on the last remaining troops. Ukrainian drone attacks gave these troops just enough time to run from their defenses to waiting vehicles behind the buildings and make their escape.

While the Russian seized the northern road, the 3rd Brigade troops were effectively cut in half and started to operate independently. Ukraine still held the southern road, the last road out, in large part because of the troops holding out at Zenit. But the Russians had advanced along a treeline north of Zenit, almost cutting them off. The garrison moved out in small groups to run the gauntlet and many of them were killed or wounded. Six wounded soldiers could not be evacuated and they were later killed by Russians.

Every Ukrainian soldier had his own experience during the withdrawal and their experiences varied based on where they were and when they evacuated. Some units were able to withdraw all their personnel, including their wounded. Others were cut off from their commanders and lost communication with each other. The Ukrainians report that Russia had their own organizational issues and that 3/4 of the Russian troops seemed to know what they were doing and 1/4 were untrained and confused. Even with the loss of organizational control, though, everyone knew their role and the junior leaders on both sides kept fighting the battle.

The Russians knew they were to attack, and their push forward was unceasing. The 110th brigade and other units that had been defending Avdiivka knew they were supposed to withdraw from one position to the next, and when a defense was no longer possible, they moved to the west. The 3rd Brigade knew their job was to be the last line of defense and stayed in their positions until all friendly troops in front of them were gone. As their perimeter shrank, troops were sent to hold the treelines outside the city to keep the southern road open. They watched as some vehicles leaving were destroyed by Russian artillery and others were hit by drones and kept on moving. When one unit in the treelines along the southern road were hit by cluster munitions, they knew it was no longer possible to hold their position. They waited for a break in the fire and then started walking west, spaced out so that one shell wouldn’t hit multiple people, and looking behind as intensely hot magnesium shells landed on their former positions just 500 meters away.

Withdrawing when you are heavily outnumbered, outgunned and in close contact with the enemy is extremely difficult. Many of the withdrawals were done at night because only some Russian drones had night vision capabilities, but the Russian commanders were still able to see the general situation even if communication with their front line units were sporadic. Without a doubt, Ukraine struggled with their own command and control issues in such a difficult situation. Ukraine initially said that at least 25 and maybe close to 100 troops were taken prisoner. Syrsky recently gave a definitive number of 25 prisoners. There were also initial reports that 1,000 were missing.

Missing could mean killed or captured, but with the deterioration of command and control between higher headquarters and the front line squads and companies, it could just mean that the status was unknown at the time. There are plenty of instances when individuals and squads were cut off and able to make it back to friendly lines. In other cases, the missing troops were never cut off but their higher command just didn’t know where they were. The number of “missing” troops, in the sense that their commanders didn’t know their status, could very well have been quite high for a period of time and could just as easily be resolved in a few hours as individuals and squads reported to their chain of command. The exact number of Ukrainian casualties were not published by credible sources, but they were certainly high by Ukrainian standards. And the Russian casualties were higher still, even by their standards.

***

The Avdiivka Retirement and Delaying Operations

The fighting did not stop when the last of the Ukrainian troops left the city. Russia was still pushing forward and Ukraine had to reestablish its defenses west of the city. Once the 110th Brigade and all the other units that were defending Avdiivka were no longer in contact with the Russian forces they retired deep behind friendly lines for a well earned rest and replenishment. The 25th Airborne and 61st Mechanized Brigades were brought in to set up defenses behind the small Durna river. To provide time, the 3rd Assault Brigade’ mission changed from being the security force in a withdrawal to a covering force in a delaying operation. The 47th Brigade to the north also gradually fell back from Stepove while bleeding the Russians along the road to Berdychi.

More important than holding on to as much terrain as possible is holding terrain that will minimize Ukrainian losses and maximize Russian losses. The river, small as it is, is one such natural barrier that would enhance a defense. Defensive positions closer to Avdiivka would be easier for Russia to attack because of the cover that the city provides. In addition, the towering structures of the coke plant that provided an observational advantage for Ukraine for many months now provides Russia that same advantage. But rather than pull back to the river immediately, Ukraine decided to defend positions as long as it provided a reasonable advantage.

The 3rd Brigade first made their stand in the villages of Lastochkyne and Sieverne. In the previous week, Russian artillery fired scatterable mines to prevent Ukrainian vehicles from withdrawing. Now these mines acted as a barrier to Russian attacks on Lastochkyne. Ukrainian drones and artillery also took their toll in destroying at least a dozen Russian vehicles and a lot of infantry. The 3rd Brigade held onto the villages for a week before pulling back to Orlivka and Tonenke.

The 61st Mechanized and 25th Airborne Brigades had moved into their defensive positions when it was decided to withdraw from Avdiivka. Already on February 16th, as the withdrawal was still underway from the city, their defensive positions were being hit by airstrikes. Artillery fire followed soon after. Around March 7th, the 25th Brigade was ready to assume complete control of its defenses and moved forward to take control of Orlivka and Tonenke from the 3rd Brigade. The 3rd Brigade then withdrew through the 25th Brigade lines and retired to a reserve position. The 25th Brigade held onto those villages for another two weeks before falling back to their present positions.

***

The Avdiivka Defenses Today

Ukraine is currently at the defensive line it wants to hold. At its closest point, it’s four kilometers away from the towering buildings of the coke plant. The city is 6-9 km from the defensive positions and in between there are treelines, open fields and villages that have been flattened by airstrikes, artillery and drones.

Russia is most successful when they can mass a large amount of infantry close to Ukrainian defenses. Large assault groups cannot mass in a treeline, which leaves the basements of the bombed out villages. Tonenke is 1500 meters away from the small river, and while Orlivka is only 200 meters away, the Russians can only assault across a 600 meter front along the river. To either side of that gap are 800 and 1300 meter wide impassable lakes. The villages where Ukraine can place logistical support is 4-6 km away when 2 km is preferable, and the defenders on the front line will still have to endure Russian airstrikes, artillery and drones, but this might be a relatively strong position (all provided it was fortified well-enough on time): an even more extensive system of trench works was constructed further to the west. The way the situation is right now, there is not enough information on what effect the artillery and air strikes may have had upon the first line along the Durna River, though.

The flow of battle will likely be similar to that of Stepove: Russian elements will move from Avdiivka to the front lines across the open fields and suffer attrition from drones and mines. When they reach a position close to the Ukrainian defenses, Ukrainian forces will try to destroy them with artillery, drones and direct fire before the Russians can create an assault unit large enough to threaten their defenses. Over time, Russian airstrikes, artillery and drones will degrade Ukrainian defensive positions. The speed at which this happens depends on how extensive the positions are, how well they are built and the intensity of the Russian attacks. Given enough Russian effort, the defensive positions will become too degraded to occupy. They will become the gray zone which Russia will try to occupy and Ukraine will try to depopulate from the safety of the next line of defensive positions. Losses will continue on both sides, but they will be very much higher for Russia than for Ukraine.

And the cycle continues.

=====

A description of retrograde operations…https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/fm/7-20/Ch5.htm

In war, all the important things are simple. And all the simple things are hard. Two of Murphy's Laws of Warfare. And people just don't get how hard some of this stuff is. "Pulling back? How hard is that to do? And the Ukrainians lost men and equipment doing it? Obviously they are incompetent and deserve to lose." I heard that a lot from lots of folks who have never worn a uniform for a single day. I wish people would actually read more stuff like this before opening their mouths.

Thanks Tom, but personally I still think that the Kherson withdrawal was negotiated between the two sides. Even after it became very clear that the Russian were withdrawing, the ZSU didn’t try to destroy the remaining units.