Good morning everybody!

Sorry for a longer hiatus: first health-issues, and then the need to catch with my work that stood idle during the health-issues kept me much too busy but to ready any reports, the last few weeks. Until somebody manages to clone me, there’s no way I can do everything at once…

Today, I’ll try to catch — or at least to start catching — with at least the most important of latest developments related to warfare in Ukraine of the last 2–3 weeks. For the start, I’ll address air warfare, because this is having an impact upon the entire war.

Please mind, after a longer break, my reporting is likely to be ‘little bit rusty’ at first: it’s going to take few days until I really catch with all the relevant news.

Sergey Surovikin

On 8 October 2022, right after announcing his ‘mobilisation of 300,000 (Shoygu) or 1,000,000 (other sources) reservists’, Putin has appointed a new commander for all VSRF (and ‘allied’) forces in Ukraine: Sergey Vladimirovich Surovikin.

Contrary to previous officers in that position, Surovikin is an officer with ‘at least some semblance of air power background’. Sure, for most of his career he served in motor rifle troops of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (VSRF). Then, from June 2016 until sometimes in summer 2017, Surovikin served as the Commander of the Russian Group of Forces in Syria. However, that’s when his career became ‘interesting’. As explained in Moscow’s Game of Poker, during his tour in Syria, Surovikin has managed several feats. He has unified the command of the Russian, Assadist, and Iranian forces in the country (so that they began seriously coordinating their operations, instead of each fighting an entirely different war); has directed the VKS-element of the Russian Group of Forces in Syria into interdicting the flow of supplies from Turkey to insurgent units on the frontlines; and has ‘successfully’ concluded the campaign of intentional targeting of civic authorities to the degree where these became dysfunctional. As a result, the insurgency found it impossible to maintain any kind of stockpiles of ammunition and supplies inside Syria; dozens of thousands of Syrians fled to Turkey; and the insurgency eventually had to withdraw into north-western Idlib. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in November 2017, Surovikin was appointed the Commander of the Air & Space Force (VKS).

IMHO, this assignement has given him a ‘better’ insight into-, and thus a better feeling for actual capabilities of modern-day air power, but also the VSRF’s arsenal of ballistic- and cruise missiles — than this was the case with other, earlier Russian commanders of forces deployed in Ukraine. It has proven his ideas for how to fight a war by such means for ‘sound’. Foremost, it has proven to Putin that he can rely on Surovikin to deliver the desired results — and thus let him command on his own, without his continuous micromanagement. Unsurprisingly, already a day after assuming his new command, Surovikin initiated a ‘missile offensive’ on Ukraine.

Strategy

The essence of Surovikin’s strategy is obvious — and ‘well-proven’ from Syria of 2015–2017: make the capability of the enemy government and state to run everyday civilian life impossible; make the life for civilians as miserable as possible — because that’s demoralising those defending them, even making them unable to fight. The latter is of particular importance considering that

a) the Russians have failed, miserably, in eight months of directly targeting the flow of Western arms and supplies for Ukrainian armed forces, and

b) the Russians were in urgent need of buying time to replace their own losses.

Time and again over the last eight months, we’ve seen — actually — ‘limited’ Russian efforts to stem the flow of supplies from the West for the ZSU through targeting the railway network, storage depots, and major companies overhauling and repairing heavy equipment for Ukrainian armed forces. In grand total, this effort cannot but be summarised as a failure: lots of ammunition was spent for, actually, little in return. Even if some damage was caused, nothing made the failure more obvious than the highly successful Ukrainian counteroffensives in northern Kherson and eastern Kharkiv of the last and this month.

These offensives have, de-facto, completed the destruction of the ‘peace-time’ VSRF: the Russian Armed Forces as they entered the war. While it remains unclear if these have lost 60,000, or up to 90,000 killed in action (KIA), and a similar number of wounded in action (WIA), certain is that they have lost about 50% of manpower and equipment of units with which they went into the war. This is what eventually forced Putin into that mobilisation.

Why is this ‘obvious’?

Check the statistics provided by instances counting visually-confirmed losses (like the Oryx blog, for example): these are clearly shown that as of 15 September, the VSRF lost about 50% of its pre-war fleet of T-72, T-80, and T-90 main battle tanks (MBTs). A combination of evidence and estimates for Russian artillery losses is offering similar results.

As next, mind that it takes time to pull reserve-vehicles and artillery pieces from the mothballs, make them operational again, train new crews, form new or rebuild battered units, and then deploy them to Ukraine. Mind that back in May, the last sober Russian military analyst, Colonel Mikhail Khodaryonok (retired), explained that it takes at least 90 days to establish, train, and equip a new armoured division (BTW, Khodaryonok warned already before invasion that Russia can’t win and when he began asking unpleasant questions on the Russia-1 channel, he was quickly silenced).

Therefore, conclusion is on hand: the secondary purpose of this aerial onslaught on the Ukrainian power supply network is ‘buy time’. Buy it through slowing down the Ukrainian build-up and the logistics; delay, postpone, at least slow down the next Ukrainian counteroffensive until recently mobilised Russian reservists are ‘ready’.

Target Selection

Contrary to Syria, where the targeted area was relatively small (it’s less than 120km from, say, the main VKS air base, Hmeimim, to eastern Aleppo), Ukraine is huge. Foremost, contrary to Syria of 2015–2017,

- when the VSRF had the ‘luxury’ of being able to squander dozens of ballistic- and cruise missiles to hit very little (up to 60% of deployed missiles were malfunctioning), and the VKS could fly dozens of thousands of air strikes while hitting next to nothing, but was unmolested by non-exiting insurgent air defences;

- but, was successful because it could continue re-striking the same targets over an extended period of time, until actually scoring hits, and

- contrary to Syria of 2015–2017, where it was enough to knock out few power lines, one powerplant, two water processing facilities, and few food storage depots (and even that took the Russians something like six months)

- in Ukraine of 2022, such an, actually, small effort would not work. If for no other reason then because Russia does not have the necessary number of ballistic- and cruise missiles on hand any more: too many have been spent in eight months of war.

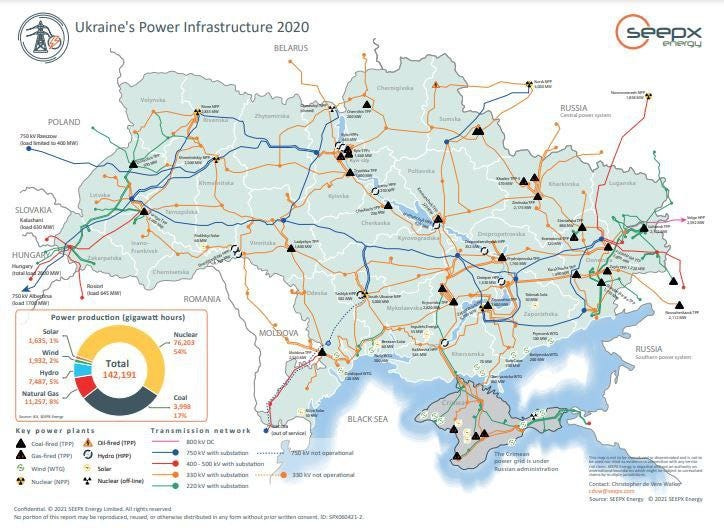

This is what made an alternative necessary: simple logic says that what Russia can do instead is to hamper the work of all of such instances — through denying them the power supply. Obviously: Russians can’t go knocking out big nuclear power plants. If nothing else, that would result in radiation that would rapidly spread into Russia, not only poison large parts of Ukraine, first and foremost. But, they can target gas- and coal-fired thermal power plants (TPPs, the number of which is limited to about 15–16), and hydro power plants (HPPs). Even easier — and more promising — is to target the power grid: this is spread over all of the country and thus not as well-protected as TPPs and HPPs. Indeed, targeting the power grid is the easiest way of accomplishing this mission: correspondingly, primary target of this ‘missile offensive’ is the Ukrainian power grid.

This became obvious already after the first day of this offensive, on 10 October, when the Russians deployed a combination of ballistic- and cruise missiles, and what the Ukrainians call ‘Kamikaze Drones’ — i.e. Iranian-made Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 ‘loitering precision guided ammunition’ — to hit (for example),

- TPP-5, TPP-6, Darnytska TPP, and Tripolskaya TPP in the Kyiv area,

- Lviv TPP-1,

- Burshtyn TPP,

- Dinpro TPP,

- Krivyy Rih TPP and similar objects.

Additionally, they have targeted transformator- and substations. For example, Vokzalna, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil, Lviv, Kremenchuk (Poltava), and two or three in the Kharkiv area.

Arguably, Ukrainians claimed 50–60% of deployed missiles and UAVs as shot down, and have provided plentiful of evidence for many of their claims. However, there is no doubt that enough of weapons ‘came through’ to hit and cause damage over the last 12 days. Foremost, after almost two weeks of this offensive, there is no denial that it is causing severe damage to both the Ukrainian power supply and the power grid. The last two days, government of Ukraine was forced to impose power cuts: the entire country is without electricity at least four hours a day. This is necessary to enable repairs, but also to lessen the burden on TPPs and HPPs that are still operational.

Hope, I need not explaining what kind of problems is this causing to the overall Ukrainian effort to continue waging this war.

….nor what an abysmal failure the West committed when failing to deliver advanced air defence weapons to Ukraine for almost eight months.

Tools

Except for the — meanwhile: critically low — number of Iskander ballistic missiles, Kh-101 and Kh-555 air-launched- and Kalibr sea-launched cruise missile, Surovikin is nowadays able to deploy a growing number of Iranian-made ‘loitering precision guided munition’ (LPGMs, essentially, UAVs pre-programmed to strike selected coordinates), especially Shahed-136; apparently, some Shahed-131, too. You might recall I’ve discussed the backgrounds and capabilities of these to quite some length, the last month:

Ukraine War, 19 September 2022: Intro to Iranian UAV/UCAVs, Part 1

Ukraine War, 20 September 2022: Intro to Iranian UAV/UCAVs, Part 2

Ukraine War, 23 September 2022: Intro to Iranian UAV/UCAVs, Part 3

Using known serials of Iranian LPGMs wreckage of which was found in Ukraine so far, a colleague from Romania assessed that Russia has got around 90 Shahed-136s alone, by now. This number is likely to increase as Iran — despite all the possible denials from official Tehran — is likely to soon ship another batch to Moscow.

Moreover, in the aftermath of a visit of Iran’s First Vice President, two senior IRGC-officials, and an official from the Supreme National Security Council to Moscow, on 6 October, there are reports about Iran being short of delivering Fateh and Zolfaghar ballistic missiles to Russia. With other words: contrary to Putin’s haphazard micromanagement of the war so far, and Dvornikov’s bloody frontal assaults, somebody like Surovikin is likely to have a better understanding of limitations of own forces, and act differently; also more likely to take better care about meaningful deployment of available assets.

Air Combats

There is circumstantial evidence that this ‘Surovikin’s missile offensive’ also has a ‘useful bi-product’: that this has forced Ukrainian Air Force to scramble its interceptors.

Ukrainian MiG-29s and Su-27s are the ‘1st line’ of air defence of the country — the tool that is usually the first to engage incoming Russian cruise missiles and UAVs — and they have shot down a number of cruise missiles and Shaheds so far.

When Ukrainian interceptors are kept busy flying intercept sorties, they cannot fly strikes with AGM-88 HARMs on the Russian air defences — like they did back in September in the Kherson area (and then with, apparently, quite some success: up to 30 hits on Buks, Pantsyrs and S-300s were reported). Moreover, when Ukrainian interceptors are busy searching for and shooting at incoming cruise missiles, they are exposing themselves to the Russian interceptors and long-range surface-to-air missiles.

Almost ‘unsurprisingly’, atop of a confirmed loss of two Ukrainian interceptors in September, reports surfaced from Russia about an Ukrainian Su-27 (and/or one Su-24) being shot down by S-300V4 SAM-systems using 40N6 or 48N6DM long-range missiles over a range of 217km, on 12 October 2022. Arguably, some Russians claim this has happened when that jet (or two jets) was (were) involved in some sort of an air strike on targets in the Belgorod area: I have my doubts about this, though.

Furthermore: some are claiming that the actual ‘killer’ was one of Su-57 prototypes, using the R-37M air-to-air missile. Hand on heart, I do not trust any kind of reports about combat deployments of Su-57s: at least I have seen no evidence for the type — precisely; the VKS might have six of them ‘in something like trials-ready configuration’ — actually being capable of running any kind of combat operations at all (not even training operations with live weapons).

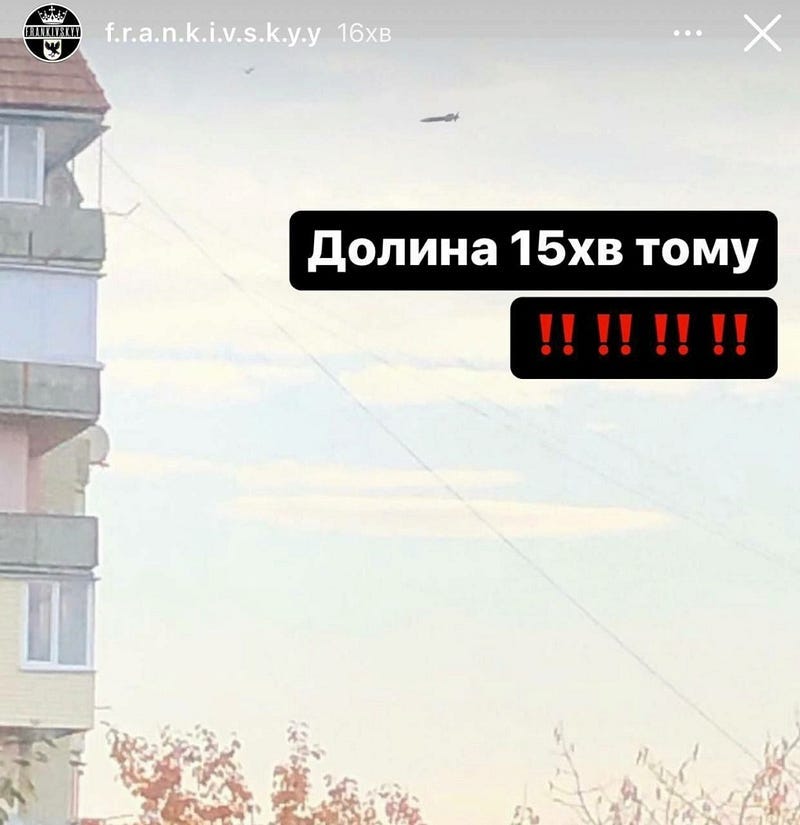

But, R-37M can be deployed from MiG-31 and/or Su-35S, too; it has a — claimed — theoretical maximum range of 400km (when released from high altitude and high speed); and one was caught on a video taken by Ukrainian civilians in the Ivano-Frankivsk area, two weeks ago. ….and let us not forget that the crash of a MiG-31 from the 790th IAP at Belbek AB, on the occupied Crimean peninsula, back on 1 October, has confirmed that the VKS is not only flying intensive combat air patrols with these, but actually deploying them ‘that close’ to the frontline, too.

Overall, there can be no doubt that the outcome of ‘Surovikin’s missile offensive’ is going to have a direct impact upon developments on the battlefield. The longer it goes on — the longer Russia proves capable of sustaining it — the more damage is Ukraine going to suffer; the more damage Ukraine suffers, the longer it’s going to take for its armed forces to continue their counteroffensives….and the longer is the war going to go on, and there is going to be yet more suffering by civilians.