The Wild Hornets: Ukrainian Volunteer Drone Production

Donald Hill's story on a private initiative that jump-started a major effort at drone production.

A volunteer organization in Ukraine, the Wild Hornets started by producing 30 drones a month in an apartment and is now making 1500 a month in a small facility with 30 people. Some of the people are volunteers without any experience and others are skilled engineers. Some of the volunteers wanted to learn how to assemble drones in case they are drafted. Most have family members on the front line.

The components are ordered and then assembled manually. Parts that cannot be ordered are created on 3D printers. A year ago, Ukraine could not meet the sudden rise in demand for polymers needed for 3D printers but domestic production can now meet the demand. A year ago, almost all the components this company used were made in China. Now, about 70% is produced in Ukraine. The batteries are standard and can be bought anywhere. Cameras, video transmitters and some antennas are bought elsewhere. The motherboards, controllers and airframes are built in Ukraine. The immediate feedback from the front lines has accelerated research and design.

Most Ukrainian drone production is civilian-based through small companies or volunteer organizations. This increases the speed at which technological changes are made. Russian production is managed by the government and they build a lot of drones, but technological changes come slowly, even when they eventually copy Ukrainian designs.

The Wild Hornets worked on 20 different models of drones that could operate in low visibility using thermal, infrared and low light optics. Based on the feedback from the front, they have settled on one model that is effective, uses infrared and is much cheaper than thermal optics. Russia conducts almost all of its logistical operations at night.

The air frames have to be put together with care so vibrations do not interfere with the gyroscope. They create their own circuit boards to avoid reliance on outside sources. At each point of the assembly of electronic components they are checked for short circuits, which could be deadly on the front lines once an explosive is attached. One batch of Russian drones killed two drone operators due to faulty wiring and the entire order was sent back to the manufacturer.

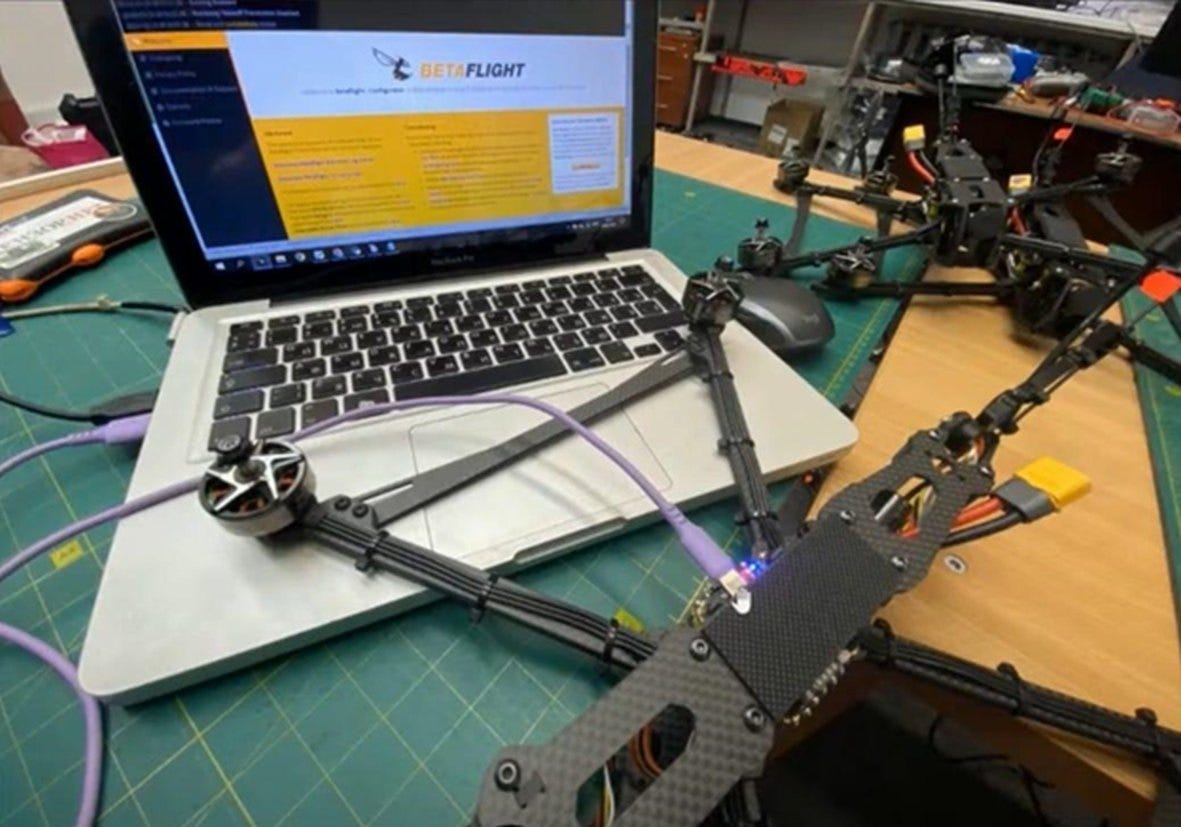

Once the drone is fully assembled, the software of the ‘hobby drone circuits’ has to be modified so that heavy munitions aren’t carried at high speeds which would quickly drain the battery. There’s also a difference between one-way kamikaze drones and bombers that fly out with one weight, and then drops its single or multiple payloads and fly back at a different weight. The electronics have to be adjusted so that control can be maintained at all the different weights.

The organization is fortunate to have access to an open field that does not interfere with air defense units and uses it to test new drone models. The munition payload often exceeds design specifications by two kilograms so they attach a non-explosive weight to the drone and fly it to see how it performs. After each flight they read the black box that records performance data and make adjustments. A skilled operator can also determine issues based on how the drone responds. The source of the vibrations could be the engines or harmonic vibration from the air frame. The air frame or speed of the engines can be altered to reduce the severity of the vibrations. Smoother flight characteristics make it easier for operators to fly. It usually takes 2-3 flights before the drone reaches optimal performance.

The 10” drone can carry 3.5 kg about 7-10 km, or 2.5 kg about 10-15 km. Vibrations will cause the engines to constantly make small adjustments which will drain the battery and reduce the range. No vibrations means a consistent and more efficient use of power. Adding filters to reduce the vibrations reduces the agility of the drone.

Before 2014, drones use in Ukraine was a civilian hobby and many of the people in the community knew each other. After the initial Russian invasion, they used their skills to aid the Ukrainian army as best they could. There is still a high level of communication among them and this company will share knowledge with anyone that needs help.

A Mavic drone has operator assistance software. When the operator stops flying it, it hovers. An FPV drone would crash. FPV drones have greater instability but in the hands of a skilled operator it provides them with greater agility. The fact that FPV drones drop to the ground when the operator lets go of the stick is very useful when chasing a moving target. Mavics are not used as kamikaze drones.

Over large distances, 10% of Russian drones reach their targets, while 20-30% of the Ukrainian drones reach their targets. The success rate for both sides increases over shorter distances. Drones use two frequencies to operate, the controller signal and the video signal. If you jam one, the operator can’t fly. If you jam the other, the operator can’t see. To change either frequency you need to have different antennas and you need to update the software, which is difficult under field conditions. This company receives feedback from the units and provides drones capable of operating on frequencies that were not jammed. (At Krynky, a Ukrainian unit (maybe Magyar) changes the software and antennas close to the front line). Russia has not demonstrated this level of agility. Frequency hopping is not used on the cheaper drones but they are planning for it in the future.

AI for terminal guidance isn’t functional right now but people outside this organization are working on it full time and the developer believes it will be functional within this year.

When a unit has enough kamikaze drones that’s all they use. When they are short of one-way drones they use bomber drones. One-way drones can reach ranges of 15 km while bombers are limited to 7-8 km. One-way drones are more precise because they can just fly into the target. Bombers need to be above the target and stable, and the camera angle needs to be changed with a servo motor. It is difficult enough to hit a stationary target with a bomber drone and almost impossible to hit a moving target. Finally, when a bomber drone returns to the operator, it can be tracked and the drone team is then vulnerable to counter battery fire.

This company doesn’t create specific drones for specific munitions, it just creates drones that can carry a certain amount of weight, creates the means to drop munitions from bombers, and creates the connection so the operator can detonate kamikaze drones. Contact detonation munitions are dangerous because if you drop the drone while handling it the operator could be killed. Remote detonation also enables airbursts, which is particularly effective against personnel. There is a delay between the operator sending the signal and the drone receiving it, so the operator has to take that into account. As a safety measure, the ability to detonate can be switched on through the motherboard after the drone is in flight.

This is a volunteer organization that does not receive money from the government. The advantage is that they move much more quickly. The disadvantage is that money is a limiting factor for the expansion of their capabilities. For those wishing to help, their contact information on various platforms is here..

https://twitter.com/ArmedMaidan/status/1766581622655123697

The 80 minute video is available here.

In Ukraine there is a society of volunteers printing parts for the military called DrukArmy https://drukarmy.org.ua/ua

Perfect article, Tom&Don! Many thanks!