The Russian Missile Campaign against Ukraine: March 2024

Adrien Fontanellaz is reviewing the Russian operations against critical infrastructure in Ukraine of the last Month.

Hello everybody!

For today, something prepared by Adrien Fontanellaz, from Switzerland.

Adrien and me are working together for nearly 10 years, and have published a number of books and articles. Indeed, over the last year, I’ve already published several of his articles on this blog. We’re currently working on a two-volumes book-project covering air warfare in Ukraine since February 2022: in that project, one of Adrien’s tasks was to analyse the Russian strikes on the critical infrastructure in Ukraine in the same year and in 2023. Unsurprisingly, the idea was thus born to start preparing ‘monthly reviews’ of such operations in more recent times. Hope, you’re going to find the results as interesting and as useful as I do.

***

Methodology

The following overview is foremost based on daily releases by the Ukrainian Air Force (PSU). As is meanwhile well-known, every day between 06.00 and 09.00hrs local time, the PSU reports what was going on the previous night and early in the morning, and reports how many incoming missiles or UAVs were detected, and how many were claimed as shot down. Arguably, this is leaving the Ukrainian air force with much too little time but to properly cross-check every claim, find and inspect the wreckage, or seriously reconstruct the events of the last night: this is often done only days or even weeks later. That said, it is meanwhile well-known that the PSU – thanks to the integration of its own integrated air defence system into that of NATO – has at least a reasonably good situational awareness about what kind of long-range ammunition are the Russian Armed Forces (VSRF) and Air-Space Force (VKS) releasing into its airspace. That, however, does not mean that the PSU is then detecting and tracking all the incoming ballistic- and cruise missiles, and all the UAVs: if for no other reason then because some are malfunctioning and crashing even before entering the zone within the reach of its radars.

Furthermore, so-called ‘overclaiming’ – exaggerated claims for own success – is a phenomenon as old as warfare. In most of faces, the fact somebody is claiming to have shot down this or that aircraft, missile, or the UAV, does not mean that the people in question are deliberately lying. For example: an operator tracking a ‘blip’ on the radar screen, denoting an enemy missile dozens of kilometres away, and then opening fire at it, cannot always reliably say this was shot down. But, if one puts oneself into the shoes of that operator, he or she has every reason in the world to consider the target as ‘destroyed’. Many times, this is also the case. However, at other times, there are other reasons why the target disappeared. It’s similar with Ukrainian teams of machine-gunners mounted on light trucks: what if two such teams open fire at the same target and shoot it down? It can easily happen that thus two different targets are claimed as shot down, perfectly in good faith.

Therefore, PSU’s claims issued in the morning must be taken for what they are: no ‘truth and the only truth’, but simply its own assessments of what was detected and what assessed as shot down the last night. This is no perfect science, but better information than nothing at all. Foremost, it’s enabling analysts to obtain invaluable hints about ‘what is going on out there, by night’.

Statistics

The Month of March 2024 has seen a marked increase in the number of missiles and UAVs released by the Russians into the Ukrainian airspace. The PSU detected and tracked at least 860 different weapons. This is even more significant considering that the PSU ceased to publish its daily releases with the nomination of the Chief Public Relations Officer of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (ZSU), on 18 March 2024. The General Staff of Ukraine is reporting about PSU’s claims of the last week, but in a much less-detailed fashion: essentially, it’s mentioning the figures only.

Nevertheless, conclusion is on hand that the 860 detected and tracked weapons is a significant increase in comparison to 502 weapons detected and tracked in February, 627 in January, and even the 819 detected and tracked in December 2023.

March 2023

The month began with the usual streams of Shahed-136 (aka their Russian version named Geran-2). Usually, these are released from the Crimea (Cape Chauda and Balaklava), Yeysk, and Prymorsko-aktharsk area (south-eastern coast of the Azov Sea), but also from the Belgorod and Kursk areas.

Whilist sometime the streams included less than 10 Shaheds in one night, the bulk of those released in March 2023 included between 15 and 42 attack drones. Moreover, the mass of them was combined with attacks with S-300 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) fired in ballistic mode: like tactical ballistic missiles. This was at least valid for attacks on facilities relatively close to the frontline: foremost the city of Kharkiv, but also a number of towns in western Donbas and in Zaporizhzhya. Less often, Shahed-136/Geran-attacks are combined with air strikes (usually flown by Su-34s) releasing Kh-59 and (more recently) Kh-69 precision guided munition (PGMs): the mass of the latter were undertaken from the directions of the Black Sea, or southern Kherson and Zaporizhzya.

The first significant change in this regards took place during the early morning of 21 March, when – after a lull of three days without any kind of air strikes, and 44 days without any kind of attacks on Kyiv – the reported 11 Tupolev Tu-95MS heavy bombers released a total of 29 Kh-101 and Kh-555 cruise missiles against Ukrainian capital. As the cruise missiles (which fly relatively slow, at least in comparison to ballistic missiles) approached the Kyiv area, the Russian ground forces then fired two ballistic missiles, too. All of these 13 weapons were shot down by the PSU. However, their debris injured at least 13 people and damaged several buildings

New Targets: Hydro-electric and Thermal Power Plants

Even more intensive was the Russian missile strike run the night later: from 21 to 22 March. This included a total of 151 different weapons:

- 63 Shahed/Geran attack drones

- 40 Kh-101 and Kh-555 cruise missiles

- 5 Kh-22/32 cruise missiles

- 2 Kh-59 PGMs

The PSU claimed 55 Shahed/Gerans, 35 Kh-101/555s, and 2 Kh-59s as shot down – which was a very good result. However, this strike was accompanied by a total of 7 Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missiles (released by MiG-31K fighters), ground launched 12 Iskander-M (quasi) ballistic missiles and 22 S-300s. All of these were fired at targets not permanently (if ever) protected by the three MIM-104 Patriot SAM-systems of the PSU: against areas defended by SAM-systems that have no anti-ballistic missile capability.

Foremost, the strike of the night from 21 to 22 March marked the start of a Russian campaign against hydro-electric power plants (HPPs) and thermal power plants (TPPs) of Ukraine. In Sumy Oblast, attacks on energy system facilities knocked out power supply to Sumy, Konotop, and Shostka. In Vinnytsia, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Mykolaiv, Odesa, Dnipro, Khemlnytsky and Poltava Oblasts there was material damage to apartment buildings and preventive shutdowns of power supply. It Kharkiv, the Russians attacked no less than 15 different objects related to the energy infrastructure: the Zmiivska TPP was completely destroyed, the Kharkiv TEC-5 combined heat- and power plant was badly damaged, and about one million citizens in the city left without electricity and water supply for the next four days. The city of Zaporizhzhya was hit by 12 missiles: the Block 1 of the Dnipro HPP was destroyed, the Block 2 badly damaged, and the overhead power line Dniprovska was cut off: in turn, the external power supply to the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant was shut down. At least five people were killed and more than a dozen injured during these strikes.

The following night, from 22 to 24 March, the Russians continued targeting the Ukrainian HPPs and TPPs – even if on a lesser scale: mostly with ‘their usual harassment’ by Shaheds, S-300s, and Kh-59s. However, on 24 March, they launched another massive attack:

- 28 Shahed/Geran attack drones

- 29 Kh-101 and Kh-555 cruise missiles

…of which 18 and 25 were shot down, respectively.

Zircon

On 25 March, an unusual incident occurred when eight missiles were fired from the occupied Crimean Peninsula, including:

- 2 at Kyiv

- 1 at Poltava

- 1 at Kremenchuck, and

- 4 at Odesa.

While results of other strikes remain unknown, at least some details about the two that have reached Kyiv are known: both were shot down. A subsequent investigation revealed that these were Zircon hypersonic anti-ship missiles, modified for deployment from the land. Apparently, both were targeting the headquarters of the Security Services of Ukraine.

As far as is known, at least one Zircon was already deployed by the Russians – back on 7 February 2024. The weapon was claimed to be ‘uninterceptable’ – even by Patriots, foremost because of its maximal speed of March 9. However, according to the Ukrainians, it turned out that during its final descent, it is reaching Mach 2.5 at most, thus remaining well within engagement envelope of the MIM-104.

Last Hurrah

On 28 March, the Russians released:

- 28 Shahed/Geran attack drones

- 3 Kh-22/32,

- 1 S-300

- (at least) 1 Kh-31P anti-radar missile.

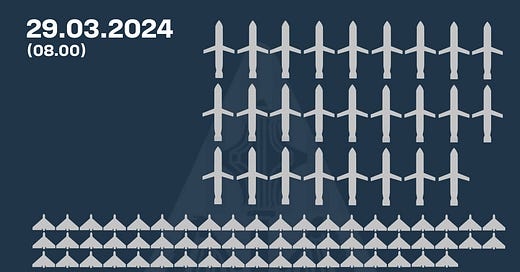

Only a night later, they released an even bigger strike:

- 60 Shahed/Geran attack drones (from two drections: Koursk and Prymorsko-Akhtarsk)

- 21 Kh-101 and Kh-555 cruise missiles (by 11 Tu-95MS)

- 4 Iskander-K cruise missiles

- 2 Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missiles

- 9 Kh-59 (released by 9 Su-34s from the Belgorod region).

The PSU claimed 17 Kh-101/55s, 4 Iskander-Ks, 5 Kh-59s and 58 Shaheds. However, none of Kinzhals were intercepted and two Iskander-Ms came through., adding to the damage on several powerplants in central and western Ukraine.

Finally, 30 March saw a smaller, ‘harasment’ attack with 12 Shahed/Gerans and four S-300s, while the strike of 31 March included 14 Kh-101/555s, 11 Shahed/Gerans (9 of which were claimed shot down by the PSU), together with a single Kh-59s and one Iskander-M.

Deductions

In grand total, through the month of March, the PSU detected and tracked 860 Russian weapons, and claimed to have shot down 634 of these, including:

- 596 Shahed/Geran: 511 shot down

- 161 Kh-101/555 cruise missiles: 119 shot down

- 102 ballistic missiles: 4 shot down.

Alone from this it is obvious that the deployment of ballistic missiles – like Iskander-M, NK-23/Hwasong-11, Kinzhal, Kh-22/32, Zircon, and S-300 remains the biggest problem. As of this month, the PSU had only one weapon capable of reliably intercepting them: MIM-104 Patriot. SAMP-T might have a similar capability but as of March, only one system was available. PSU’s manned interceptors – like MiG-29s and Su-27s – were primarily deployed to counter the Russian Shahed/Geran attack drones and cruise missiles: at least four of their actions were recorded during the month.

The Russian decision to re-initiate the campaign against the Ukrainian energy sector might sound counterproductive considering this would have been much more vulnerable early this year, during the winter. Thus, it is on hand that it actually came in retaliation for Ukrainian drone attacks on the Russian oil sector (i.e. refineries). From the Ukrainian point of view, it is certainly a worrisome development, because the energy supply system is the very fundament of any nation, on which the function of all activities is dependable.

At least the experiences from the month of March gave reasons for doubts about the – so far – highly-praised and even feared Zircon. Moreove,r not a single Kalibr cruise missile was launched by the units of the Russian Black Sea Fleet (in comparison, at least eight Kalibrs were launched in January and February): the latter fact is indicative of the success of the protracted Ukrainian campaign of targeting enemy warships by anti-ship missiles and seaborne drones.

That said, if there is any good news in all of this, then that the VSRF and VKS have spent their pre-war inventories of ballistic- and cruise missiles. The pattern of their deployment through March is quite certain to reflect the output of their production facilities. Indeed, with the last earlier massive Russian air strikes taking place in late December 2023, it is quite likely that from January to March 2024, their industry has manufactured a total of 307 cruise missiles and 98 ballistic missiles (including 30 Kinzhals, with the rest being Iskander-Ms, additional to few NK-23s). Unsurprisingly, the emphasis in such operations was actually on Shahed/Geran attack drones, of which 1,337 were released during March. From that point of view, the Ukrainian decision to strike the factory in Yelabuga, on 2 April 2024 – was a reasonable decision.

Hi Adrien, thanks for your analysis and Tom for sharing. . .

Thanks for the analysis.

To me, the use of ballistic missiles is a classic asymmetric warfare case: an attacking country may stock hundreds of ballistic missiles compared to dozens of Patriot missiles in anti-ballistic roles (both regarding cost and number of missiles).

So, the real deterrence happens when the defending country also has an adequate number of ballistic missiles to cause harm to the attacker. Unless Ukraine has a large amount of ballistic missiles able to hit within the Russian territory and against Russian military targets (launchers etc), I think that the whole fight is quite one-sided. Depending only on defensive measures is a recipe for losing the war.