(…continued from Part 2…)

Equipment

18 RCH 155 - wheeled, self-propelled, howitzers calibre 155mm - should arrive in Ukraine in 2025. This system has a range of 40 km and a crew of two: https://en.defence-ua.com/weapon_and_tech/germany_to_provide_ukraine_with_the_rch_155_howitzers_by_2025_is_there_way_to_accelerate_production-5338.html

Russia received 1.53 million rounds of 122mm and 152mm from North Korea so far: Mapping North Korea’s discreet Artillery Ammunition Route to Russia.

The deliveries of Skynex Germany are working well (even if slow), and another is on the way in March. Here it is firing in a demonstration environment: https://twitter.com/deaidua/status/1751694785478361324

Tactical Drones

Pilotless aircraft have been around for a while. In 1849, Austria launched 200 unmanned balloons over Venice with time-fuses for bombs thesee were carrying. Sure, only one did land in the city, while the wind carried many back over Austrian lines. At the end of First World War the allies experimented with unmanned aircraft that used gyroscopes, and others that were radio controlled. They even flew planes that would stop the propeller after a certain number of rotations, causing the aircraft to crash on the ground after passing approximately the desired distance - essentially, much like notorious German V1 missiles of the Second World War.

Iraq was the first country in the Middle East to introduce to service what is also known as ‘UAV’ - unmanned aerial vehicle - when it acquired a number of US-made target drones in 1957. Later on, during the Vietnam War, the US Air Force flew 3,435 reconnaissance missions by drones over North Vietnam, losing 554 of them. In more recent times, not only Israel and South Africa, but also Iran flew reconnaissance drones in its war with Iraq of the 1980s, and in 2002, a Predator drone fired a Hellfire missile that killed the alleged mastermind of the bombing of the US Navy’s destroyer USS Cole (DDG-67).

In 2014, in response to the first Russian invasion, Ukrainian volunteers started developing reconnaissance drones for the army and within a year they became an official military unit. However, in 2020, the resulting force was reduced in size and split into SBU and cyberwarfare sections, when Ukraine transferred 20,000 people from active to reserve status.

From September to November of 2020, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought what is also known as the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. The first conflict ended in 1994 with a clear Armenian victory. However, over the following 26 years, Azerbaijan used its oil revenues to provide its army foremost with more accurate and longer-ranged artillery. Moreover, it integrated reconnaissance- and so-called FPV-drones (stands for ‘first person view’). Azerbaijani armed forces thus began deploying their drones to detect Armenian movement and positions, and to direct fire of own artillery, which began destroying Armenian artillery, tanks, and fortifications; and located targets for the FPV drones. The short war ended in an overwhelming Azerbaijani victory. Rather unsurprisingly, only four months later, Ukrainian Army reinstated its own drone unit.

Although aerial warfare is mostly associated with air combat and bombardment, the biggest contribution of air power to the First World War was within realms of reconnaissance - and to counter-reconnaissance (because aircraft were first armed for air combat with the purpose of shooting down enemy reconnaissance aircraft). This remains valid until today. For example, out of US$32 billion the USA have spent during its short involvement in the First World War, no less than US$1.7 billion (or 5%) were used to expand its air power, and much of this dedicated to aerial reconnaissance. In similar fashion, from the US defence budget of 2022, which was worth US$754 billion, no less than US$54 billion (or 7%) were spent on satellites with military purpose.

More than hundred years since the end of the First World War, there are interesting parallels to the development of aerial warfare in this conflict. Drones and their munitions are doing a lot of what manned aircraft used to do from 1914 to 1918, and one can monitor not only their development, but also the development of their armament and equipment, and the purposes for which drones are deployed. And, as one technology emerges, others are becoming obsolete. In this regards, there is no denial that drone warfare in the War in Ukraine is pointing at the things to come.

During the First World War, the German Empire managed to gain temporary strategic advantage through deploying its Zeppelin dirigables into a bombing campaign. In the 1930s, this resulted in the emergence of the school of thought that the strategic bomber would dominate the future conflict and win easy victories by annihilating enemy urban- and economic centres. Certainly enough, combat experiences from the Second World War have shown that this is anything else than easy to achieve, and comes at a heavy price, but still: not only that Great Britain invested up to one third of its defence budget of 1944 and 1945 to build-up its strategic bomber force, but the USA followed in fashion. Ultimately, the deployment of the nuclear bomb led some to believe that conventional ground combat was rendered only a minor role, and fighter aircraft and tanks were declared obsolete. Of course, not only that the Korean War proved all such theories as completely wrong, or nuclear weapons for ‘non-practical’ in too many conflict scenarios: it remained many of the fact is that there is no ‘Wunderwaffe’ that can win all the wars.

Another fact is that drones are playing an ever increasing role in the observation and destruction of enemy forces. It is a ‘combat-multiplier’. The performance of automatic grenade launchers, mortars, artillery, rockets, missiles - and other drones, too - is significantly enhanced thanks to the deployment of reconnaissance drones, the purpose of which is to find potential targets and then correct the first. The influence of drones on the battlefield in Ukraine is such that nowadays it is almost impossible to mass a large number of troops and equipment to conduct a surprise assault on a weak sector.

For example, because of UAVs, Ukraine’s offensive into eastern Kharkiv of August-September 2022 was no surprise to Russia: the build up was observed and reported by the front line Russian troops but Russian command simply did not react to it.

Certainly enough, many think that the deployment of the means for electronic warfare would promptly deny access to the enemy drones. In reality, fact is that deploying electronic warfare for anti-drone purposes on even a small section of the battlefield is very hard - and frequently disturbing own operations as much as those of the enemy. With other words: even electronic warfare is no fail-safe solution. Because of this, in the War in Ukraine, both parties are constantly having their eyes on each other.

One estimate is that as of early 2023, artillery - usually supported by reconnaissance drones - used to cause up to 90% of casualties in this conflict - and that on both sides. This estimate was meanwhile reduced to around 70%: neither side can sustain the necessary production rates for artillery ammunition, and thus this branch is increasingly replaced by ever more numerous drones.

That said, if the supply would not be an issue, neither side would be forced into choosing between artillery and drones: it would pick both. Moreover, drones alone cannot win a war: for effective operations, they require being deployed like every other weapon - like tanks, infantry, artillery, mines, and other assets - in cooperation with other armament, always depending on requirements.

Nowadays, the situation on the battlefields in Ukraine is such that, once detected by the enemy, any column of 6-10 vehicles loaded with infantry moving towards the front line must be expected to become the primary target for (devastating) artillery strikes aiming to destroy, or at least immobilise vehicles, and kill, wound, or at least pin-down the infantry. Survivors are then regularly picked by attack drones.

Drones are deployed for offensive purposes, too: for striking enemy field fortifications. They are particularly effective in attacks on small dugouts, or narrow trenches: in this regards, they are proving much more effective than classic, massed artillery strike - although the latter retains the advantage of the weight of fire and the speed of of impact: reason is that ‘converted hobby drones’ are much easier and cheaper to manufacture than artillery shells, while offering much higher precision - and this although it often takes up to five drones to completely destroy, or just immobilise and armoured vehicle.

Ukraine has never had enough artillery ammunition, and thus remains unable to target every enemy column it detects - whether by artillery or by drones. Despite such examples like recently at Snkivka, where Javelins were once again highly effective in spoiling another Russian armoured assault, Ukraine remains critically short on such weapons, too - just like it is short on tanks and infantry fighting vehicles like M2/M3 Bradleys, which proved highly effective in local counterattacks (foremost in the Avidiivka area). With the access to the US production being interrupted because of the war in the Middle East and political differences in Washington DC, the ZSU has even less artillery ammunition than this was the case up to September: this in turn is forcing Ukrainians to be ever more reliant on drones.

Drones have two major advantages: they are cheap and available in large numbers from local production. Their low costs is enabling Ukrainians to acquire them in large quantities. However, just like in the case of artillery shells, the supply of drones is already-, and is going to remain, a major issue - and this issue is going to become ever more critical the more Ukraine is reliant on drones. Not only because they are the best tool for the job, but because meanwhile it is a matter of fact that they are the best available tool, highly versatile, and pretty effective.

In spring of 2023, Kyiv reported to be expending some 10,000 drones a month - whether due to losses or through attacks by FPV-drones. By December 2023, Ukraine reportedly increased its production to 50,000 drones: if the rate remains the same through this year, it would result with some 600,000 drones. However, production is constantly increasing and Ukrainian aim is to manufacture 1,000,000 tactical drones - some 2,700 per day - by the end of 2024.

Increasing the production is not the sole solution: one should keep in mind that Ukrainians will have to continue improving their drones all the time, because a drone that was effective six months ago is likely to be rendered entirely useless as soon as the enemy develops suitable methods of electronic warfare…

It is not only that the production output increased by 100 times since the Russian invasion: the number of major enterprises involved increased from 35 in 2022, to 200 in 2023. At least 50 different companies are manufacturing just the ammunition for drones. This massive growth caused a shortage in qualified personnel: Ukraine urgently needs about 2,000 engineers proficient in avionics, electronic warfare, computer vision, and digital signal processing. It also needs personnel proficient at developing embedded software and executing mathematical modeling. In the absence of such personnel, Ukrainians are using people without any knowledge and giving them intensive training on the job - but: this still, and regularly, lasts up to six months.

Russia uses its cheaper drones differently: Ukraine is using its FPVs to destroy the enemy equipment and personnel, while Russia is using its FPVs to conquer territory.

Of course, the Russian FPV-drones are deployed for attacks on Ukrainian infantry and vehicles, too, but the Russians are expending a lot of their drones to target defensive positions, such as trenches and houses: to - partially - replace their artillery, in attempt to conserve its ammunition. Considering Russia is producing about six times the amount of drones Ukraine is, and considering Ukraine is losing a lot less equipment to drones than Russia is, even when factoring in lower quality drones and pilots, it gives you some idea of how many drones Russia is using on defensive positions. Without the defensive positions, Ukraine has to withdraw and Russia can advance.

With so much of the skilled workforce fleeing Russia, it is not only possible, but even likely that Moscow is experiencing similar personnel-related problems like Ukraine. Nevertheless, just one of major companies there is reporting a production rate of 1,000 drones a day, and Moscow claims to be manufacturing up to 300,000 drones a month. That means that already now, the Russian armed forces have six drones for every Ukrainian drone: this ratio might decrease to something like 4-for-1 by the end of this year - all provided Kyiv really manages to increase its output.

Like in Ukraine, there seem to be no automated production line in Russia: rather 3D printers and up to 20 stations per company, where workers use soldering irons and electric screwdrivers for assembly.

The Russians are boasting that 90% of their components are made at home: this is likely to be truth. However, the remaining 10% are a major issue, because - for example - Russia has no production of computer processors, and thus had to import these, whether from the West (in most of cases), or from the People’s Republic of China and elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, Russian troops are reporting very different quality of their drones: some are poor and unsuitable for the constantly changing battlefield, others are excellent. It is almost certain that such issues are caused by the lack of skilled engineers.

The increased deployment of drones requires both the Russian and Ukrainian armed forces to adapt their training, too. For example, in 2023, Russia reported to have trained 3,500 drone pilots and was training another 1,700.

Except for RPVs, both Ukraine and Russia have more expensive drones that can destroy enemy equipment 70-80km behind enemy lines. At US$35,000 each, the Lancet is Russia’s high quality FPV. While devastating to civilian utility vehicles and ambulances, it doesn’t always kill military equipment on the first hit, but it’s deadly enough that the Ukrainians camouflage their vehicles when stationary and check the skies while driving. The Russians recently began using a limited number of Scalpels, a drone that looks similar to the Lancet but costs mere US$3,300. It only has a range of 40 km instead of 60-70 km, and it flies at 120 km/h instead of 300 km/h, but if it’s still effective then Russia can buy ten of them instead of one Lancet.

Russia doesn’t send its Lancet drones behind Ukrainian lines unless they’ve spotted a target first, and for that they have the Orlan-10, which costs around $150,000, can fly for 16 hours and has a range of 110 km. It can fly up to an altitude of 5000 m, which is out of range of many of the cheaper air defense missiles. A year ago, Ukraine said they shot down 580 of them. I haven’t seen any reports on production rates but they aren’t running out of them and Russia said (a year ago) that they had “58 surges”, which probably means increases to the production rate.

One of the first drones the Ukrainians bought was the Turkish Bayraktar TB.2. Compared to the US $30 million MQ-9 Predator/Reaper, at US$5 million it was inexpensive and instrumental at spotting for artillery strikes in the early weeks of the war. There were up to 20 TB2s in Ukraine before February, 2022, although not all were able to fly. Media reports say Ukraine received 50, but that figure may have included the 20 they already have. There was even talk in October 2022 of producing the TB.2 in Ukraine by 2024, but as Russian operations became more organized, EW and air defenses started taking their toll on the drone. Ukraine says that it can only fly the TB.2 in ‘certain situations’, indeed, a colonel in the SBU said last November, ‘For the TB.2, I don't want to use the word useless, but it is hard to find situations where to use them’. This is making it unlikely that any might be deployed in high-threat environment - and thus also that money might be spent, and any of precious factories might be kept busy manufacturing them.

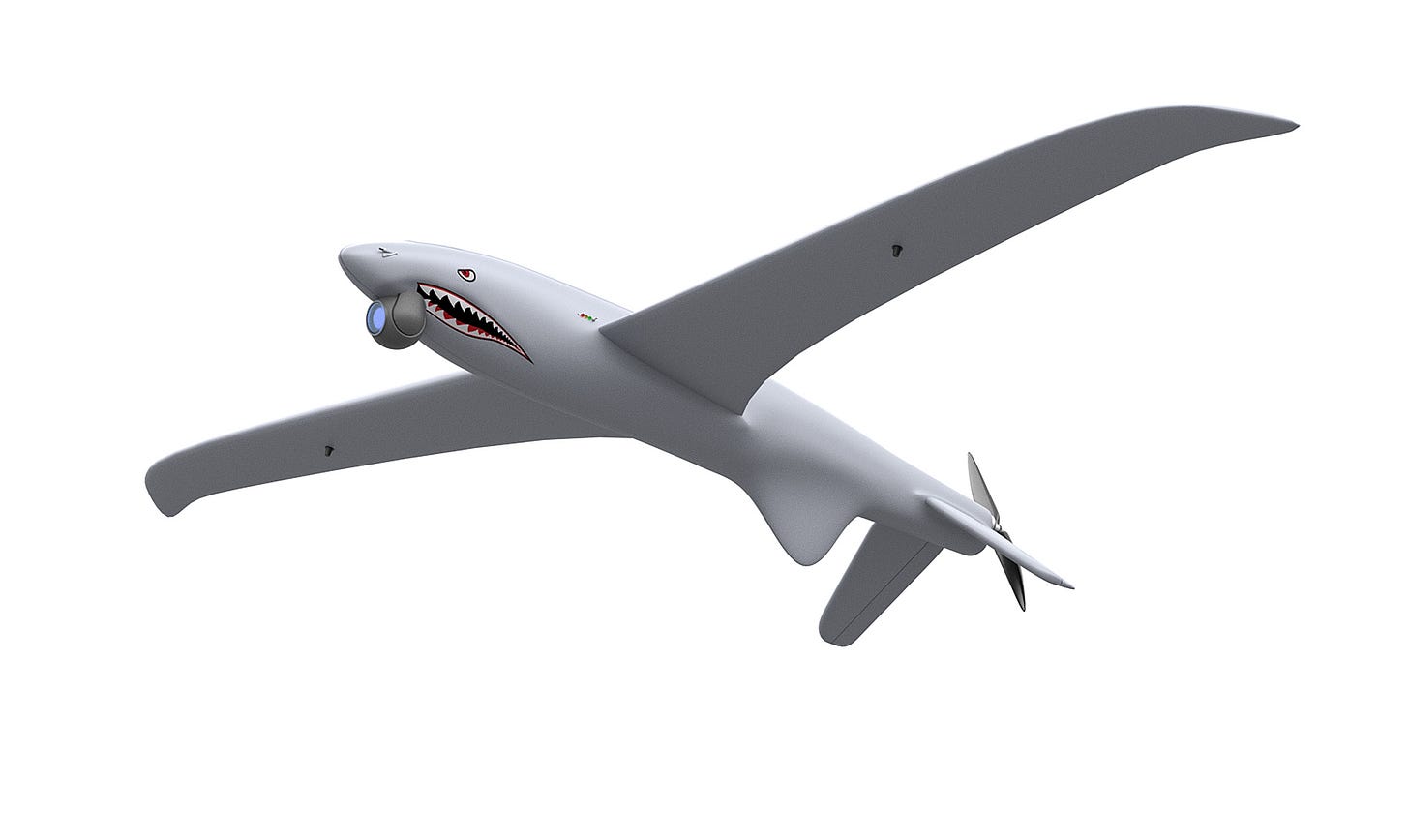

Ukraine is constantly developing and testing new drones and concepts and one of the successful models has been the Shark reconnaissance drone. Each costs about US$120,000, and is resistant to electronic warfare jamming and circuit burnouts and can view targets from 5 km away. It has an operation ceiling of 3000 meters and an 80km-communication-range, and is regularly deployed for finding targets for M141 HIMARS systems (and their M31 rockets), which has a range of 84km. However, exactly like Orlan, it cannot operate at ambient temperatures colder than -15°C (5°F).

This will be the first winter for many of Ukraine’s drone designs. Some will perform better than others. Ukraine’s drone production is more diverse and quicker to innovate and respond to the changing battlefield, but the state is just recently committed to the mass production necessary for their mass production. That said, Zaluzhny said that they need technology as a combat multiplier to break out of static warfare and he says they’ll have the necessary amount of equipment to conduct operations by July. It will be interesting to see what actually happens.

Russian drone production reflects the characteristics of its army. It produces a lot and most of it pounds Ukraine’s defenses over time until they no longer exist, and then the army advances 1-2 kilometers. It achieves a certain amount of local success. In the meantime, Ukraine is destroying artillery, tanks, APCs and IFVs faster than Russia can produce or refurbish them. Russia still has enough equipment for quite some time, but if the war and these trends continue for a couple more years then Russia will run out of equipment long before Ukraine runs out of territory.

https://mil.in.ua/en/news/kamyshin-ukraine-produced-50-000-fpv-drones-in-december/

https://media.defense.gov/2010/Oct/13/2001329759/-1/-1/0/AFD-101013-008.pdf

https://www.nber.org/digest/jan05/economics-world-war-i

https://www.ukrmilitary.com/2020/09/aerorozvidka.html

https://www.reuters.com/world/turkeys-baykar-complete-plant-ukraine-two-years-ceo-2022-10-28/

Thanks for the drone discussion.

The distributed (and not mass-produced) system for making drones in Ukraine might be a blessing in disguise. Having a central drone factory would be a very tempting target for Russian missiles.

Like troop training/generation and tank manufacturing, the huge size of Russia offers an advantage to them.

Also, the Russian drone use for getting more territory (by demolishing fortifications) mirrors the use of the other assets (personnel, tanks etc) - getting territory is the name of the game for Russia. And they're ready to spend a huge amount of military resources for this.

(with more and more howitzers arriving in Ukraine, from RCH 155 and CAESAR to Pzh2000 etc), the problem might not be the number of guns anymore, but the ammunition.

Another superb report (both), thank you